Lecture 22 in the series Introduction to NT Textual Criticism, "The New Testament in the Marketplace," is online at Bitchute and YouTube. In this 22-minute lecture, I offer a critique of some methods used to market the NIV and other versions, especially the claim that the KJV's base text is late and minimally attested. I review the basis for the KJV's readings in Matthew 17:21, Matthew 18:11, Matthew 20:16, Matthew 23:14, Mark 6:11, Mark 7:16, Mark 9:44, 9:46, Mark 11:26, Mark 15:28, Luke 17:36, Luke 23:17, and John 5:3-4, and draw attention to some non-Alexandrian English versions of the New Testament such as the EOB (Eastern Orthodox New Testament). Here is an extract:

In 1971, the preface to the RSV was very candid in its criticism

of the KJV. It stated, “The King James Version has grave defects.” It

also stated that the Greek base-text of the New Testament in the KJV was “marred by mistakes containing the

accumulated errors of fourteen centuries of manuscript copying.” It stated that the King James Version’s base-text

was essentially the text as edited by Beza in the late 1500s, and that Beza’s text

closely followed the work of Erasmus, “which was based upon a few medieval

manuscripts.”

This was technically

true, but it is not the whole truth.

This incomplete caricature is still used in the promotion of several translations

of the New Testament. The King James

Version is very frequently misrepresented, as if it is only supported by a

smattering of late medieval manuscripts.

People are told that scholars today “Now possess many more ancient

manuscripts of the New Testament” than were known in the 1500s.

There are some

minority readings in the Textus Receptus. At Acts 9:5-6, the Textus Receptus has a harmonization that, as far as I can tell, is

not supported by any Greek manuscripts.

In Ephesians 3:9 and Philippians 4:3, readings in the Textus Receptus look like the effects

of spelling-mistakes in the manuscripts

used in the 1500s. In First John 5:7-8,

the Textus Receptus has a reading

that originated in a branch of the Old Latin text, and which only appears in a

few late manuscripts as far as Greek copies are concerned. But these readings do not drastically alter

the character of the text: fewer than 700

readings in the Gospels in the Textus

Receptus are not supported by a majority of Greek manuscripts.

Materials written

to promote new versions routinely avoid drawing attention to the strong level

of agreement between the Textus Receptus

and the majority of Greek New Testament manuscripts. It is not the Byzantine Text, but the Alexandrian Text, that routinely

disagrees with over 90% of the Greek manuscripts.

But you would

never realize this if you relied upon the marketing of modern Bible versions

such as the New International Version. Marketers

of modern versions routinely describe the Nestle-Aland base-text as if it is based

on very many ancient manuscripts.

Instead of

focusing on the agreements of the Textus

Receptus with the majority of manuscripts in the Gospels, Acts, and

Epistles, attention is given to the most recent layers of corruption in the Textus Receptus: as Eberhard Nestle pointed out in 1898: do we really want to offer readers a text of

Revelation that was based on a single manuscript? Do we really need to go on distributing a

text in which the last six verses of Revelation were based on Latin? Is the Textus

Receptus really the best compilation that can be produced?

Clearly the

answer is no. I have no doubt that

Erasmus and Stephanus would agree. But I

am not convinced that they would agree that the need to refine their work justifies

throwing out the Byzantine Text and replacing it with the Alexandrian Text,

which is what is done by the NIV. Misrepresentation

of the quality and age of the Byzantine Text is a tactic that has been used in many

attempts to get people to embrace the Alexandrian Text. This was done in the 1800s, and it is still

attempted today.

For example, Biblica,

formerly known as the International Bible Society, has produced a video called

“Is the NIV Bible Missing Verses,” which asks the question, “How did the KJV and other earlier Bibles

end up having more words than ours do today?”. Biblica’s presentation conveys that

differences between English versions exist because the Biblical researchers in

the 1500s only had a few manuscripts, which were not very early – but researchers

today use many more manuscripts that are much more ancient.

Specifically, Biblica tells viewers that the main manuscripts used by the producers of the Textus Receptus were just a few hundred

years old, only going back to the twelfth century. In comparison, today’s scholars have “almost

6,000” manuscripts. In addition, the

manuscripts Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus provide a “much earlier” text.

But viewers are not told that the text in the vast

majority of those thousands of manuscripts is Byzantine, which means that in most textual contests where the

Alexandrian and Byzantine forms disagree, they support the Byzantine reading,

and disagree with the Alexandrian form.

In other words, they tend to oppose

the base-text upon which the New International Version is based.

In addition, viewers

are not told how soon the Byzantine readings are supported. Instead, they are given the impression that their

choice is between readings from the 300s, and readings from the 1100s, so, of course they will tend to prefer what

they are led to believe is the reading with much earlier support.

Let’s take a

close look at some readings in the Gospels that are included in the King James

Version, but are not included in the New International Version – not to delve

into the intricacies of each textual contest, but to test how honest, or how dishonest, it is to tell people that when

we look at these readings, we are looking at a text from the 300s as the basis

for the NIV, versus a text from the 1100s as the basis for the KJV.

(1) Matthew 17:21 is not

in the text of the NIV. It is supported

by over 99% of the Greek manuscripts of Matthew, including Codex D and Codex

W. It is also supported by most of the

Old Latin copies of Matthew including Codex Vercellensis. It is supported by the Vulgate, and was cited

by Origen, who died in the mid-200s – before

Vaticanus and Sinaiticus. Other

patristic writers who used this verse include Hilary, Basil, Ambrose,

Chrysostom, and Augustine, representing five different locales.

(2) Matthew 18:11 is not

in the text of the NIV. It is supported

by the vast majority of manuscripts, including Codex D. It is also supported by the Vulgate, and by

the Peshitta. It was in the text used by

Chrysostom.

(3) The second part of

Matthew 20:16, “For many are called, but

few are chosen,” is not in the text of the NIV. It is supported by most Greek manuscripts of

Matthew, including Codex D, and by the Vulgate, and the Peshitta, and it was used

by Chrysostom. An additional

consideration is that the final letters of the final word in this phrase are

the same as the final letters in the word that comes before this phrase, which

could make the whole phrase vulnerable to accidental loss via periblepsis.

(4) Matthew 23:14 is not

in the text of the NIV. It is supported

by the majority of Greek manuscripts of Matthew, including Codex W. It was quoted by Chrysostom, and is included

in the Peshitta. Another point to

consider is the potential of this reading to be accidentally lost via

periblepsis, because it begins with the same opening word as the verse before

it, and the verse after it.

(5) The last part of Mark

6:11 is not in the text of the NIV or the ESV.

It is supported by the vast majority of Greek manuscripts of Mark,

including Codex Alexandrinus. It is also

supported by the Gothic version and the Peshitta.

. . .

(11) Luke 23:17 is not in

the text of the NIV. It is included in

most Greek manuscripts of Luke, including Codex Sinaiticus and Codex W. It is supported by the Old Latin text, the

Vulgate, and the Peshitta.

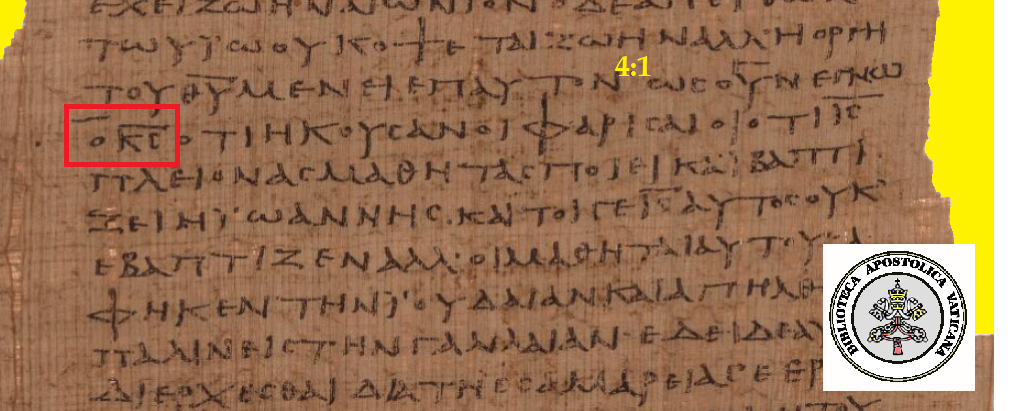

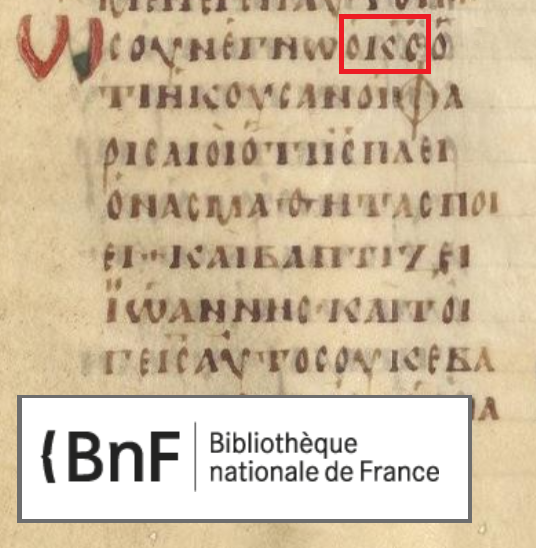

(12) John 5:3-4 is not in

the text of the NIV or the ESV. It is

included in most Greek manuscripts of John, including Codex Alexandrinus. Tertullian, writing in about the year 200,

seems to have used a text of John that has this reference to an angel at the

pool of Bethesda. It inclusion is also supported by the

Peshitta, and by Chrysostom in his Homily

36 on John.

More than nine

times out of ten in the Gospels, where a verse or phrase is included in the King

James Version but is not in the NIV, its inclusion is supported by the majority of Greek manuscripts, and support for the KJV’s reading can be

seen in evidence from the 300s, the same century when Codex Vaticanus and Codex

Sinaiticus were made.

It is simply not

true that the verses and phrases that are supported by the Byzantine Text typically

only appear in late medieval manuscripts.

Claims that promote the idea that the KJV’s readings typically originate

in the 1100s or later should be regarded as propaganda.

In addition, it should

be pointed out that when marketers of the NIV refer to the high number of Greek

New Testament manuscripts as an “embarrassment of riches,” they are strangely

celebrating the abundance of evidence against

the text that they promote, since the vast majority of Greek manuscripts

support the readings that are not in the text of English versions such as the

NIV, the ESV, the NLT and the NET.

The base-text of

the NIV is often described as an “eclectic” text. By definition, an “eclectic” compilation

takes all transmission-branches into consideration. But in terms of its content, at points where

the Alexandrian Text and the Byzantine Text disagree, the Nestle-Aland

compilation adopts the Byzantine reading less than 1% of the time.

The Nestle-Aland

text represents the local text of Egypt, especially as represented by

Vaticanus and Sinaiticus, from the fourth century. Support for many Byzantine readings is just

as old, or only slightly later. For some

Byzantine readings, it is earlier.

What about

papyrus manuscripts? Papyrus manuscripts

from the 200s confirm the earlier use of the Alexandrian Text in Egypt. We do not have papyrus evidence from other

locations. But, unless one wants to

propose that Christians in the 300s spontaneously threw out the copies of

Scripture that their predecessors had endured persecution to protect and preserve,

the alternative is to reckon that there were

papyrus manuscripts in Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey, and Syria in the 200s,

and that they were the ancestors of manuscripts used in the 300s and 400s which

contained many Byzantine readings.

The

humidity-level in Italy, Greece, Cyprus,

Turkey, and Syria is not

conducive to the preservation of papyrus – but it is not equitable or

reasonable to ignore the text from this area because of the weather. The

early stratum of the Byzantine Text deserves attention, especially the readings

preserved in writings by individuals such as John Chrysostom, Gregory of Nyssa,

Basil of Caesarea, Cyril of Jerusalem, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, and others.

This does not

mean that future investigation of the text that was used in the northeastern Roman Empire in the 300s and 400s will vindicate every

reading found in the majority of Greek manuscripts. It won’t.

But the earliest discernible stratum of the Byzantine Text deserves much

more attention than it has received in the so-called

“eclectic” compilation upon which the NIV is based.

There are

alternatives to English translations that are based on the 99% Alexandrian Nestle-Aland

compilation. Some Bible-readers, particularly

in the United States,

have reacted to the challenge posed by new versions by answering all

text-critical questions with one response: “The King James

Version is always right.” That response is not

scientifically sustainable, and in many cases it is fueled by a tendency to

stick to the New Testament translation one is used to, whether it really is

based on the original Greek text or not.

Other

Bible-readers, acknowledging non-original elements in the Textus Receptus but regarding them as fairly benign, have decided

to stick with the King James Version, on the grounds that although its

base-text is far from perfect, it has been shown to be sufficiently accurate as an English representation of the meaning

of the original text.

For Bible-readers

who desire their English translation to conform to the original text as closely

as possible, rather than be inordinately limited to the local text of Egypt, the

challenge posed by the rise of versions based on a pseudo-eclectic base-text

should be met by the application of a more equitable eclectic method of textual

criticism – an approach that is not biased against the idea that the original

text may be found in the Byzantine Text.

With that in mind, I refer you to the following four English

translations.

The base-text of

the New Testament in the Evangelical Heritage Version, released in 2017, is far from consistently Byzantine, but

its editors have taken the Byzantine Text seriously. Of the 12 readings reviewed in this lecture,

the EHV includes seven of them in the text.

The text of the EHV also includes Mark 16:9-20, Luke 22:43-44, all of

Luke 23:34, and John 7:53-8:11. More

information about the Evangelical Heritage Version can be found at wartburgproject.org – that’s W-a-r-t-b-u-r-g-project.org,

all one word.

The Eastern Orthodox New Testament reflects

an awareness of the critical text in its footnotes, but consistently favors the

Byzantine Text. It can be purchased from

New Rome Press, and it can be read online, for instance at the website

yorkorthodox.org/bible . The text of the

EOB includes all of the readings reviewed in this lecture, and also includes

Mark 16:9-20, Luke 22:43-44, all of Luke 23:34, and John 7:53-8:11.

The World English Bible is a copyright-free

translation of the Old Testament and New Testament. Its New Testament was intended to be based on

the Majority Text. It is available as a

free PDF download at https://worldenglish.bible/ and is also available in

print.

In addition, if

you read the New King James Version

and pay special attention to its textual footnotes, especially where readings

in the Majority Text are mentioned, it will be similar to reading a version

based on the Byzantine Text.

Thank you.