Clement of Alexandria is one of the

best-known writers of early Christianity; although we lack details of his birth

and death, an estimate of 150-215 is probably not far off. He was trained at Alexandria

by Pantaenus, and after Pantaenus died, Clement began to lead the catechetical

school at Alexandria,

around A.D. 200.

Clement

of

Alexandria

left behind several compositions in which he quoted, referred to, or otherwise

used many passages from the New Testament.

By putting together these Scripture-utilizations, we may get a picture

of the New Testament text that Clement used.

By working through Clement’s

Hortatory

Address to the Greeks and Paidagogus

and Stromateis and Hypotyposeis and What

Rich Man Can Be Saved?, and other compositions, it is possible

to isolate Clement’s Scripture-utilizations and tentatively reconstruct the

text he used.

One might expect to find that Clement

used a New Testament with strong Alexandrian affinities – after all, he was

located in Alexandria. But back in 2008, Carl Cosaert analyzed

Clement’s Gospels-text and acknowledged that “Clement fails to meet the 65%

rate of agreement necessary for classification as an Alexandrian witness in the

Gospels.”

One might expect to find that Clement

used a New Testament with strong Alexandrian affinities – after all, he was

located in Alexandria. But back in 2008, Carl Cosaert analyzed

Clement’s Gospels-text and acknowledged that “Clement fails to meet the 65%

rate of agreement necessary for classification as an Alexandrian witness in the

Gospels.”

In

Matthew, Cosaert’s analysis indicated that although Clement’s text agrees with

Sinaiticus more than with any other manuscript – at 73 out of 116 units of

variation – Codex Π was a very close second, at 68 out of 109, and Codex Ω was

a very close third, at 72 out of 118.

This is statistically a tie. But

it is not just a tie between these three witnesses. Cosaert also compared Clement’s text of

Matthew to the Textus Receptus – and

it performed as well as Codex Vaticanus (B):

the Textus Receptus agreed

with Clement’s text of Matthew 73 times out of 118 units of variation (61.9%);

Codex B agreed with Clement’s text of Matthew 71 out of 117 units of variation

(60.7%).

In Mark,

Cosaert’s analysis indicated that Clement’s text agrees more with the Textus Receptus – 29 times, out of 47

units of variation – than with À (21/42) or B (25/47).

The data from Clement’s utilizations from Mark is, however, rather

sparse: fewer than 50 units of variation, stretched over 16 chapters, are extant to consider.

In Luke,

Cosaert’s analysis indicated that Clement’s text agrees more with Codex D than

with any other Greek manuscript – 89 agreements out of 134 units of variation.

In comparison, Codex Ω agreed with Clement’s text 77 out of 143 units of

variation; P75 agreed with Clement’s text 62 out of 116 units of variation, and

Codex Π agreed with Clement’s text at 74 out of 140 units of variation.

In John,

Cosaert’s analysis indicated that Clement’s text agrees more with Codex L than

with any other witness – 54 agreements out of 72 units of variation. Manuscripts 33, B, and P75 (all between with

a 70-75% agreement-rate) also agree with Clement’s text of John more than Π, Ω,

and the Textus Receptus (which all

hover around 60%). Codex À does

even worse, though, with an agreement-rate of only 54.3%.

Cosaert’s

data instructively illustrates two things.

First, it shows that it is precarious to draw conclusions based on

sporadic sampling: we cannot know the

textual affinities of Clement’s text of Matthew by looking at his text of John,

and we cannot know Clement’s text of Luke by looking at his text of Matthew. Analyzing a patristic writer’s text is not

always as simple as putting one knife into one jar one time and concluding that

the whole jar contains peanut butter. Clement’s Gospels-text is not comparable to a

horserace in which one horse wins; it is more like four horse-races in which the

outcome is different in every race: In

Mark, the Byzantine text seems to win; in Luke, the Western text comes out

ahead; in John, the Alexandrian text wins, and in Matthew, the race is close

and ends in a cloud of dust.

Second, it

shows that there is not much basis for the idea that the text of Clement’s

compositions has been corrupted (toward a Byzantine standard). Had this been the case, we would not see

Western affinities in Clement’s text of Luke, or such strong Alexandrian affinities

in Clement’s text of John.

With all that in mind, let’s turn to

another piece of research on the text used by Clement:

Maegan Gilliland’s 2016 doctoral thesis at

the University of Edinburgh School of Divinity:

The Text of the Pauline Epistles

and Hebrews in Clement of Alexandria.

(Use the link to download the thesis!)

This is a very detailed piece of research; Gilliland presents a

book-by-book apparatus of Clement’s utilizations of each of Paul’s epistles,

collated against representative witnesses of each text-type.

Although neither the

Robinson-PierpontByzantine Textform nor the

Hodges-Farstad Majority Text was included in the

comparison, the Byzantine Text is well represented by minuscule 2423, a

manuscript housed at

Duke

University.

Although it

would be worthwhile to take a leisurely tour of Gilliland’s thesis

book-by-book, today I want to zero in on the data it contains about Clement’s

text of First Thessalonians. First

Thessalonians is a rather small book, containing only five chapters; in these

five chapters Gilliland has identified 32 variant-units utilized by

Clement.

Before

proceeding further, let’s briefly revisit Cosaert’s data for the Gospel of John: 72 variation-units are stretched across 21

chapters. The witness with the strongest

agreement with Clement was Codex L (54/72) and after also observing that

Clement’s text of John agrees with 33, B, and P75 about 70-75% of the time,

Cosaert concluded, “Clement’s strong levels of agreement with the Alexandrian

tradition clearly identify his text as Alexandrian.” I want to make sure that it has registered

that with one Alexandrian witness agreeing with Clement’s text 75% of the time

over 21 chapters, and with three Alexandrian witnesses agreeing slightly less,

Clement’s text of John was clearly identified as

Alexandrian.

Now let’s

look at Gilliland’s data about Clement’s text of First Thessalonians: Gilliland compared Clement’s use of readings

in 32 passages: 1:5, 2:4, 2:5, 2:6, 2:7,

2:12, 4:3, 4:4, 4:5, 4:6, 4:7, 4:8, 4:9, 4:17, 5:2, 5:4, 5:5, 5:6, 5:7, 5:8,

5:13, 5:14, 5:15, 5:17, 5:19, 5:20, 5:21, 5:22, 5:23, and 5:26.

No

utilizations were detected from chapter 3, and only one utilization – the use

of a single word, δυνάμει in Str. 1.99.1 – was detected in 1:5 (and it seems to me

that this could be a utilization of First Corinthians 4:20 instead). If we set that aside, then Clement’s

references to First Thessalonians cover only 2:4-12, 4:3-4:9, 4:17-5:8, and

5:13-5:26. The existence of 30

utilizations concentrated in four segments, consisting of 11 verses, 7 verses, 10

verses, and 14 verses – a total of 42 verses – ought to be a plentiful basis on

which to form an impression of the form of Clement’s text of First Thessalonians. This is especially true when we remember that 72

utilizations, stretched over 879 or 866 verses (depending on which compilation one is using), were considered sufficient to tell us

about Clement’s text of John. (A

rough-and-ready picture of the situation may be gained by considering that in

these four segments of text from First Thessalonians, Clement gives us no data

about 12 verses, in the Gospel of John Clement gives us no data about 794

verses (at least).

Gilliland found that the medieval Byzantine

minuscule 2423 agrees with Clement’s utilizations in First Thessalonians in 29

of the 32 variation-units – yielding an agreement-rate of 91%.

This

justifies Gilliland’s statement (on p. 542 of her thesis) that “A glance at

the individual manuscripts reveals a strong association between Clement’s text

of 1 Thessalonians with the Byzantine manuscripts,” and (on p. 543), that

Clement’s text of First Thessalonians “exhibits a text that is strongly aligned

with the Byzantine tradition.”

However, in the fifth chapter of

Gilliland’s thesis, on p. 567, she states, “Perhaps the unusually high

agreement with the Byzantine text is only a fluke resulting from a small data

set.” One page later, she states less

tentatively, “There simply are not enough variation units for 1 Thessalonians

to come to any conclusion about its textual nature,” and suddenly, “Clement’s

text of I Thessalonians cannot be labeled as Byzantine.”

The apparent reason for this sudden

shift: an “Inter-Group Profile” shows

that Clement agrees with no Byzantine readings in First Thessalonians that are distinctly Byzantine; it also shows that

Clement agrees with no Western readings that are distinctly Western, and it also shows that Clement agrees with one

distinctly Alexandrian reading.

But let’s take a close look at the differences

between the text of First Thessalonians in the Byzantine Text, in Clement’s

text, and in Codex Vaticanus, to see if this reasoning is sound. First, we should notice that in First

Thessalonians 2:6, the Byzantine Text (Robinson-Pierpont) reads ἀπό rather than

ἀπ’. (The Textus Receptus there reads ἀπ’, agreeing with 2423 and

Clement.) Second, we should notice that

in First Thessalonians 5:8, where 2423 appears to includes ὑιοι, the Byzantine

Text does not. Compared to 2423, the

Byzantine Text thus loses one agreement in 2:6 and gains one agreement on 5:8;

its net rate of agreement is thus the same as that of 2423: out of 32 opportunities to agree with

Clement, the Byzantine Text agrees 29 times.

The Textus Receptus agrees

with Clement even more: 30 agreements

out of 32 opportunities to agree.

Besides the Byzantine Text’s reading

ἀπό instead of ἀπ’ in 2:6, the Byzantine Text also disagrees with Clement’s

text at three points:

● 4:5 – Byz has θεόν where Clement

has κυριον, but because all of the flagship-witnesses disagree with Clement,

this variation-unit was set aside.

● 5:5 – Byz does not have γὰρ after

πάντες

● 5:6 – Byz has καὶ before οἱ λοιποί

● 5:8 – Byz has σωτηρίας at the end

of the verse, where Clement has σωτηριου, but because all of the

flagship-witnesses disagree with Clement, this variation-unit was set aside.

Codex Vaticanus, in comparison,

disagrees with Clement’s text of First Thessalonians at

● 2:5 – B does not include ἐν before

προφάσει

● 2:7 – B (and À) has

ἀλλα instead of ἀλλ’

● 2:7 – B (and À* and

P65 and C*) has νήπιοι instead of ἤπιοι

● 2:7 – B (and C and 1739) has ἐὰν

instead of ἂν

● 4:5 – Byz has θεόν where Clement

has κυριον, but because all of the flagship-witnesses disagree with Clement,

this variation-unit was set aside.

● 4:6 – B (and À* and

A and 33 and 1739) does not include ὁ before κύριος

● 4:7 – B has ἀλλα instead of ἀλλ’

● 4:8 – B (and A and 33 and 1739*)

does not include καὶ

● 4:8 – B (and À*)

reads διδόντα instead δόντα

● 5:7 – B has μεθυοντες where all

other flagship-manuscripts have μεθυσκόμενοι,

However, Clement does not agree with Clement at this point: in Paed. 2.80.1, Clement uses

μεθυοντες, while in Strom. 4.140.3 μεθυσκόμενοι is used.

● 5:8 – Byz has σωτηρίας at the end

of the verse, where Clement has σωτηριου, but because all of the flagship-witnesses

disagree with Clement, this variation-unit was set aside.

● 5:19 – B has ζβέννυτε instead of

σβέννυτε

B has important Alexandrian support

in six of these readings; in four cases B and À* agree. It thus seems undeniable that no amount of spin can prevent the conclusion that Clement’s text

of First Thessalonians really is much more Byzantine than Alexandrian.

Post-script:

Two Translation-Impacting Variants in First

Thessalonians

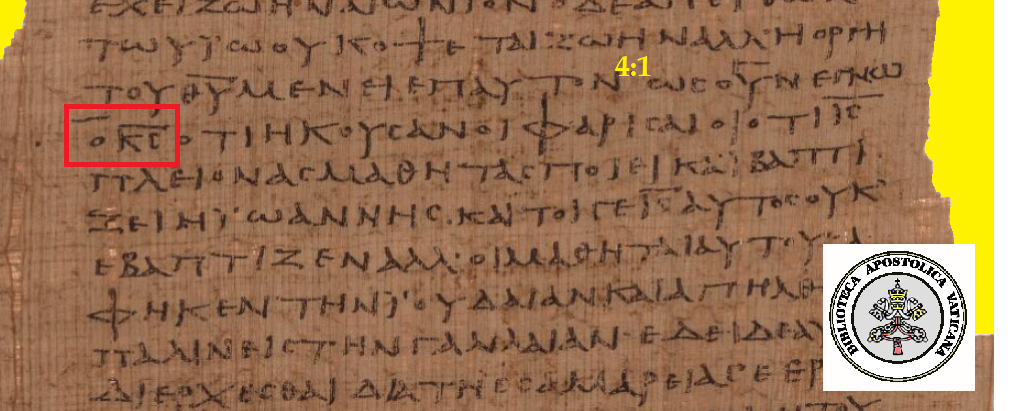

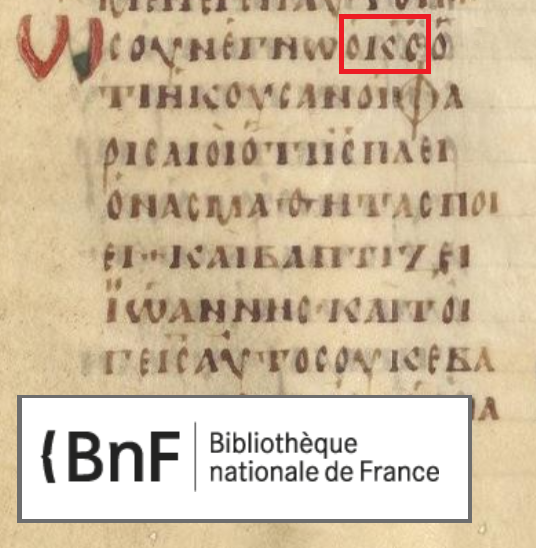

First Thessalonians 2:7 contains a

textual variant that has a potentially drastic effect on the meaning of the

verse: does Paul say “we were gentle

(ἤπιοι) among you” (as in the KJV, NKJV, ESV and CSB), or does he say “we were

like young children (νήπιοι) among you” (as in the NIV and NLT; the NLT does

not have the word “young”)?

Bruce Metzger, from the first

edition of his handbook The Text of the

New Testament, used this textual variant-unit to illustrate a contrast of

external and internal evidence to his students.

“Gentle” (ἤπιοι) has broad support from witnesses such as A K L P 33 the

Peshitta, the Sahidic version, Clement, and Chrysostom; “infants” (νήπιοι) also

has diverse support from P65, À* B C Old Latin, the Vulgate, the Bohairic and Ethiopic

versions, and patristic writers such as Cyril and Augustine.

Metzger explained that because the

preceding word, ἐγενήθημεν (“we were”), ends with the letter ν, it would be

easy for the letter ν to be added to ηπιοι, creating “νήπιοι” – and it would

also be easy for the letter ν to be phonetically dropped from νήπιοι, creating

ἤπιοι. After presenting both sides of

the issue, Metzger gave a verdict in favor of ἤπιοι, appealing to Daniel Mace’s

axiom that no manuscript is as old as common sense – that is, considering that

the transcriptional probabilities seem about equal, one should consider what

the author is likely to have written, and this consideration favors ἤπιοι. It is intrinsically unlikely that Paul would

suddenly drop the idea, like lightning from a clear sky, that he and his

associates had behaved like babies, and in the next breath say that they had

been like a nursing mother cherishing her children.

Nevertheless, despite Metzger’s

lucid argument – which he later restated in a protest-note in his Textual Commentary – he was outvoted by

his colleagues. Today, the reading in

the Nestle-Aland/UBS compilation is (incorrectly) νήπιοι.

First

Thessalonians 4:8 contains two overlapping textual variants: (1)

the inclusion or non-inclusion of καὶ followed immediately by (2) a

contest between διδόντα and δόντα. The

reading καὶ δόντα (supported by Clement and the Byzantine Text) may account for

the rise of καὶ διδόντα and διδόντα: an

early copyist whose uncial-writing was less than ideal wrote KAIDONTA but the first

A was mistaken for a Δ, as if he had written

KΔIDONTA. Subsequently, the

letter K was regarded either as a stray letter and removed (leaving what was

then understood as διδόντα (found in Codex B), or else it was regarded as a kai-compendium, which was then expanded

into καὶ before διδόντα (read by À*).

One may see a progression from καὶ

δόντα to διδόντα in sync with progression from Clement to Origen.

For reference:

Griesbach and Scholz had καὶ δόντα; Tregelles

and Westcott-Hort and Nestle (1899) and Souter adopted διδόντα (without καὶ); Holmes’

SBL-GNT reads καὶ διδόντα; one wonders by what reasoning this longer reading was

preferred. The Tyndale House Greek New Testament

correctly reads καὶ δόντα.

Readers are invited to double-check the data in this post.