Peiresc’s agents, Théophile Minuti and Jacque-Auguste

de Thou, wrote to Peiresc that they had managed to recover some items from the

shipwreck, including a small box which held an assortment of small relics, coins,

and medals, and a vellum codex (which turned out to be a Coptic lectionary) that

had survived fairly intact, thanks to the several layers of envelopes in which

it had been packaged. But these were

merely souvenirs compared to the other valuable Egyptian antiquities that the

ship had been carrying.

The disaster of the sinking of the Ambassadrice was greatly regretted at the time – but soon

forgotten. It was not until recently

that interest in excavating the remains of the Ambassadrice gained momentum, when Barry

Clifford – the American responsible for

the recovery of the wreck of the pirate ship Whydah – was recruited by the

government of

When specialists in the salvage operation carefully heated and removed the wax, they found several items were embedded within, including the manuscripts that Peiresc’s agents had obtained in

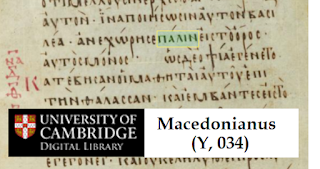

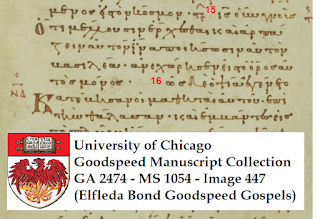

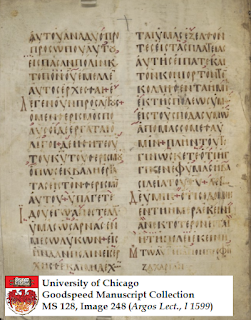

— Eight Coptic texts of the Gospels, two of which are in jeweled bindings

— An early Greek-Bohairic lectionary, prefaced by a glossary of rare Bohairic words.

— A Sefer Torah scroll,

— A hitherto-unknown composition by Dioscorus (bishop

of

— A hitherto-unknown composition by Peter Mongus of

— An incomplete parchment copy of Breviarium by Liberatus of Carthage (500s).

The sixth slab contained four ornate ivory diptychs, with the hinges removed, all carved with scenes from the life of St. Anthony. With them were numerous Egyptian and North African coins from different eras, a silver aspergillum, a gold and silver buckle inlaid with lapis lazuli, and several amulets and rings.The texts recovered from the Ambassadrice are scheduled to be published soon in a yet-untitled open-access book from Brill Academic Publishers, and the other items will be the subject of a series of forthcoming articles in Biblische Zeitschrift. In addition to an undisclosed payment for his supervision of the underwater salvage operation, Barry Clifford was awarded the Medal for Service to the Republic of Malta. Addition information about the salvage of the Ambassadrice can be found in Maltese news-articles here and here.

Happy April Fools Day 2022!

.