(Continuing the Glossary of Textual Criticism)

Diorthotes: The

proof-reader and general overseer of the production of manuscripts in a

scriptorium.

Dittography: A scribal mistake in which what should be written

once is written twice. This can describe

the repetition of a single letter, a line, or even (rarely) a whole paragraph.

Eusebian Canons:

A cross-reference system for the Gospels,

devised by Eusebius of Caesarea to help readers efficiently find and compare

parallel-passages (and thematically related passages).

The basic idea is that numbers were assigned

to every section of every Gospel, and each number was put into one of ten

lists, or canons, in a chart at the beginning of the Gospels.

The first list presented the

identification-numbers of passages in which parallels exist in all four

Gospels; the tenth list presented the identification-numbers of passages which

appear in one Gospel only, and lists 2-9 present the identification-numbers of

passages in combinations of Gospels (such as Matthew+Mark+Luke).

The

Eusebian Canons were

often prefaced by Eusebius’ composition

Ad Carpianus, in which an explanation was given of how to use the

cross-reference chart.

In some Greek

manuscripts, some Latin manuscripts, and especially

in Armenian manuscripts,

the Eusebian Canons are elaborately decorated. In a few deluxe copies, the text of

Ad Carpianus appears within a quatrefoil frame.

Also, in

some manuscripts, the copyists have put extracts from the Canon-tables below

the main text, relieving the reader of the need to consult the Canon-tables in

order to identify parallel-passages.

This is called a foot-index,

because it appears at the foot of the page.

Euthalian Apparatus:

A collection of supplemental study-helps and

systems of chapter-divisions for Acts and the Epistles, developed by an

individual named Euthalius (who to an extent adopted earlier similar materials

prepared by Pamphilus).

Little is known

about Euthalius and the extent to which his initial work has been adjusted and

expanded by others; the detailed analysis

Euthaliana, by J.

A. Robinson, remains an imperfect but valuable resource on the subject.

Family 35:

A

cluster of over 220 manuscripts which represent the same form of the Byzantine

Text.

Wilbur Pickering has reconstructed

its

archetype.

Flyleaves: Unused pages at the beginning and end of a

manuscript. In some cases, these pages

consist of discarded pages from older manuscripts, glued into or onto the

binding.

Genre distinction: The practice of recognizing each genre of

literature in the New Testament (Gospels, Acts, Epistles, and Revelation) as

having its own transmission-history.

Gregory’s

Rule: An arrangement of the

pages of a manuscript in such a way that the flesh-side of the parchment (i.e.,

the inner surface of the animal-skin from which the parchment was made) faces

the flesh-side of the following page, and the hair-side of the parchment (i.e.,

the outer, hair-bearing surface of the animal-skin from which the parchment was

made) faces the hair-side of the following page.

Only a few manuscripts, such as

059, do

not have their pages uniformly arranged in this way. (Named after C. R. Gregory.)

Harklean Group: A small cluster of manuscripts which

display a text of the General Epistles which is related to, and strongly agrees

with, the painstakingly literal text of the

Harklean Syriac version (which

was produced in A.D. 616 by Thomas of Harkel, who made this revision of the

already-existing Philoxenian version (which was completed in 508 as a

revision/expansion of the Peshitta version) by consulting Greek manuscripts in

a monastery near Alexandria, Egypt which he considered especially accurate).

The core members of the Harklean Group are

1505, 1611, 2138, and 2495.

Some other

manuscripts have a weaker relationship to the main cluster, including

minuscules 429,

614, and

2412.

Although

the Greek manuscripts in the Harklean Group are all relatively late, they appear

to echo a text of the General Epistles which existed in the early 600s, and

perhaps earlier, inasmuch as

Codex

Sinaiticus (produced c. 350) contains in the third verse of the Epistle of

Jude a reference to “our common salvation and life,” a reading which appears to

be a conflation between an Alexandrian reading (“our common salvation”) and the

reading of the Harklean Group (“our” (or “your”) “common life”).

Headpiece: A decorative design accompanying the

beginning of a book of the New Testament in continuous-text manuscripts, and

sometimes accompanying the beginnings of parts of lectionaries. These may sometimes be extremely ornate,

especially in Gospel-books.

Homoioarcton: A loss of text caused when a copyist’s line

of sight drifted from the beginning of a word, phrase, or line to the same (or

similar) letters at the beginning of a nearby word, phrase, or line. Often abbreviated as “h.a.”

Homoioteleuton: A loss of text caused when a copyist’s line

of sight drifted from the end of a word, phrase, or line to the same (or

similar) letters at the end of a nearby word, phrase, or line. Often abbreviated as “h.t.” (Many short readings

can be accounted for as h.t.-errors,

such as the absence of Matthew 12:47 in some important manuscripts.)

Initial: A large letter at the beginning of a book or

book-section, especially one enhanced by special ornateness and color. In some Latin codices an initial may occupy almost an entire page.

Interpolation:

Substantial non-original material added to

the text by a copyist.

Although

patristic writings utilize several saying of Jesus that are not included in the

Gospels,

Codex

Bezae is notable for its inclusion of interpolations in Matthew 20:28 and

Luke 6:4.

Due in part to Codex Bezae’s text’s

tendency to adopt longer readings, Hort proposed in the 1881 Introduction to

the Revised Text that Codex Bezae’s shorter readings in Luke 24 are original,

and that in each case, the longer reading is not original, despite being

supported in all other text-types.

Hort

labeled D’s text at these points “

Western

Non-Interpolations.”

Itacism: The interchange of vowels, such as the

writing of ει itstead of ι, ε instead of αι, and ο instead of ω.

Jerusalem Colophon:

A note which, in its fullest form, says,

“Copied and corrected from the ancient manuscripts of

Jerusalem preserved on the holy

mountain.”

Fewer than 40 manuscripts

have this note, including Codex Λ/566, 20, 117, 153, 215, 300, 565, 1071, and

1187; in

157

it is repeated after each Gospel.

Kai-compendium: An abbreviation for the word και, consisting

of a kappa with its final downward

stroke extended.

Kephalaia: Chapters.

In most Gospels-manuscripts, each Gospel is preceded by a list of

chapters:

Matthew has

68 chapters; Mark has 48, Luke has 83,

and John has 18 or 19. Chapter-titles typically appear at the top (or bottom) of the page on which they begin, with the chapter-number in the margin.

Lacuna: A physical defect in a manuscript which results in a loss of text.

Lectionary:

A book consisting of sections of Scripture for

annual reading.

Scripture-passages in

lectionaries are arranged according to two calendar-forms:

the movable feasts, beginning at Easter,

contained in the

Synaxarion, and the

immovable feasts, beginning on the first of September (the beginning of the secular

year), contained in the

Menologion.

Lectionary Apparatus: Marginalia and other features added to New

Testament manuscripts in order to make the manuscripts capable of being used in

church-services for lection-reading. These

features usually include a table of lection-locations before or after the

Scripture-text. Symbols are inserted in,

or alongside, the text of each passage selected for annual reading: αρχη for “start,”

“υπερβαλε” for “skip,” “αρξου” for “resume,” and τελος for “end.” Rubrics are sometimes added to identify

readings for Christmas-time and Easter-time, and holidays considered especially

important by the scribe(s). Incipits, phrases to introduce the

readings, often appear alongside the beginning of lections, or alongside the

rubric in the upper or lower margin.

Letter-compression:

A method writing in which letters are

written closer to each other than usual, and some letters are written in such a

way as to occupy less space than unusual,

This indicates that the scribe was attempting to reserve space. It occurs especially on cancel-sheets made to

remedy omissions by the main scribe.

Majuscule: A manuscript in which each letter is written

separately and as a capital. These are

also known as uncials. Many majuscules,

or uncials, are identified by sigla (singular:

siglum) such as the letters of

the English alphabet, letters of the Greek alphabet, and, for Codex Sinaiticus

(À),

the Hebrew alphabet. All uncials are

identified by numbers that begin with a zero.

Miniature:

An illustration, often (but not always)

situated within a red frame.

The term

has nothing to do with the size of the illustration; it is derived instead from

the red pigment,

minium,

which was often used to render the frame around the picture.

(This pigment was famously used in the Book

of Kells to make thousands of small dots in the illustrations.)

Miniatures of the evangelists frequently

appear as full-page portraits, showing each evangelist in the process of

beginning his written account; John is typically pictured assisted by

Prochorus.

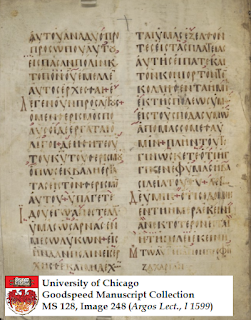

Minuscule: A manuscript in which the letters of each

word are generally connected to each other.

The transition from majuscule, or uncial script, to minuscule script, occurred

during the 800s and 900s, and was led by Theodore the Studite. Uncial script was still used, however, for

lectionaries in the following centuries.

Mixture:

A combination of two or more text-types

within the text of a single manuscript.

When mixture occurs, it normally is manifested as readings from one

text-type sprinkled throughout a text which otherwise agrees with another

text-type.

In

block-mixture, distinct sections represent distinct

text-types.

Codex W exhibits

block-mixture; in Matthew and in Luke 8-24 its text is almost entirely

Byzantine, but other text-types are represented in the rest of the

Gospels-text.

[Continued]