In the Evangelical Heritage Version, Matthew 17:21 says, "But

this kind does

not go out except by prayer and fasting.”

The KJV, NKJV, EOB-NT, MEV, WEB, and 1995 NASB read similarly. In the RV 1881, ASV, ESV, NIV, NLT, and NRSV,

however, there is no such verse; the versification jumps from 20 to 22. What has happened?

|

| Bruce Manning Metzger |

Bruce Metzger did not spend many words

explaining: “Since there is no good

reason why the passage, if originally present in Mathew, should have been

omitted, and since copyists frequently inserted material derived from another

Gospel, it appears that most manuscripts have been assimilated to the parallel

in Mk. 9.29.” (Textual Commentary on the GNT, p. 43) His concise treatment is unsatisfactory for

at least three reasons, first of which is the consideration that Matthew

himself when using Mark’s Gospel (or something closely resembling it) had no

discernible reason to skip over this statement of Jesus.

Second, the external evidence merits a

closer look.

Neither the apparatus in

the UBS GNT nor the Nestle-Aland NTG is sufficient.

We begin with their data, supplemented by

Swanson:

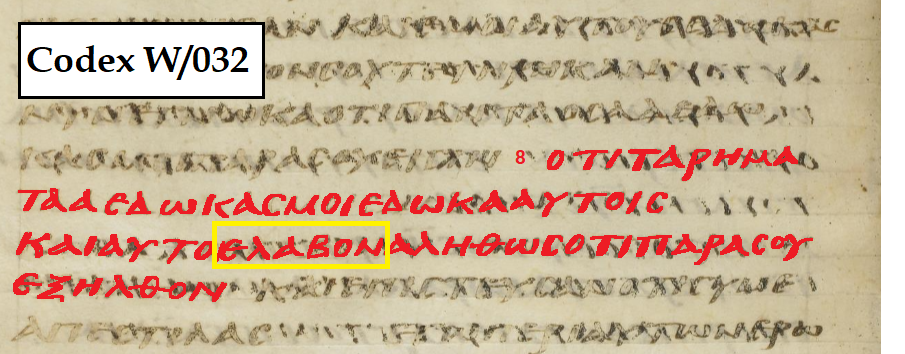

verse 21 is absent in

À* B Q 579 788 892* l253 ite ff1

the Sinaitic Syriac, the Curetonian Syriac, Palestinian Aramaic, the Sahidic

version, some Bohairic witnesses, an Ethiopic witness, and an early strata of

the Old Georgian version. Everything else favors the inclusion of τοῦτο δὲ τό γένος ούκ ἐκπορεύεται

εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ (Àc reads ἐκβάλλεται instead

of ἐκπορεύεται, 118 reads ἐξέρχεται, and 205 1505 l1074 read εξέρχεται) – including C D F G H K L Y

O W Y Δ Σ Φ 0281 f1 f13 28 157 180

565 597 678 700 892c 1006 1010 1071 1241 1243 1292 1342 1424 Byz Lect ita

itaur itb itc itd itf itff2

itg1 it1 itn itq Vulgate Peshitta

Harklean Syriac Armenian some Georgian, and the patristic evidence is lopsided

in favor of inclusion: Origen Asterius

Basil-of-Caesarea Chrysostom Hilary Ambrose Jerome Augustine. Hort noted that daemonii is sometimes added in Old Latin

witnesses. The writer of an article at NeverThirsty

stated, “The verse is not

included in the newer Bibles because the older and better manuscripts of

Matthew do not include it”

and “Apparently in the process of copying the manuscripts, someone at a much

later date copied the verse from the Gospel of Mark and added it to the Matthew

account. “

Now let’s zoom in on some patristic

witnesses.

In 2010 Jonathan C. Borland presented a paper titled “THE AUTHENTICITY AND INTERPRETATION OF MATTHEW 17:21”

at a gathering of the Evangelical

Theological Society in Atlanta,

Georgia. He noted that 1604 2680 should be

added to the list of MSS favoring non-inclusion, and that the percentage of

Greek MSS favoring inclusion is 99.4%.

He also took a close look at some

patristic witnesses:

● The author known as Pseudo-Clement,

in Letters on Virginity (1:12) did

not specify which Gospel he was quoting but the wording looks more like Matthew

17:21 than Mark 9:29 when he wrote

against individuals who “do not act with

true faith, according to the teaching of our Lord, who hath said: ‘This kind

goeth not out but by fasting and prayer,' offered unceasingly and with earnest

mind.’”

● Clement of Alexandria, c. 200, in Extracts from the Prophets, wrote, “The Savior plainly declared to the believing apostles

that prayer was stronger than faith in the case of a certain demoniac, whom they

could not cleanse, when he said, ‘Such things are accomplished

successfully through prayer.’”

● Tertullian, in de Jejun 8:2-3, without specifying

whether he was citing Matthew or Mark, wrote the following: “After that, he prescribed that fasting

should be carried out without sadness. For

why should what is beneficial be sad? He taught also to fight against the more

fierce demons by means of fasting. For is it surprising that the Holy Spirit is

lead in through the same means by which the sinful spirit is lead out?”

● Origen, in his Commentary on Matthew (13:6-7) wrote, “That

those, then, who suffer from what is called lunacy sometimes fall into the

water is evident, and that they also fall into the fire, less frequently

indeed, yet it does happen; and it is evident that this disorder is very

difficult to cure, so that those who have the power to cure demoniacs sometimes

fail in respect of this, and sometimes with

fastings and supplications and more toils, succeed.” And, “But let us also attend to this, ‘This kind goeth not out save by prayer and

fasting,’ in order that if at any time it is necessary that we should be

engaged in the healing of one suffering from such a disorder, we may not

adjure, nor put questions, nor speak to the impure spirit as if it heard, but

devoting ourselves to prayer and fasting,

may be successful as we pray for the sufferer, and by our own fasting may

thrust out the unclean spirit from him.”

● The Latin writer Juvencus wrote in Book 3

of Libri evangeliorum quattuor, “For by means of limitless prayers it is faith and much fasting

of determined soul that drive off this kind of illness.”

Although

defenders

of modern versions have claimed that “The verse is not included in the newer Bibles

because the older and better manuscripts of Matthew do not include it,” antiquity

in this case favors inclusion: the oldest

witness for inclusion is older than the oldest witness for non-inclusion.

The scope of attestation also favors inclusion at least as

much as it favors non-inclusion: Western

witnesses for inclusion far outnumber the Western witnesses for non-inclusion,

and they are geographically widespread.

We are left with the appeal to the “best” manuscripts as

the basis for rejecting the verse. But

this is circular reasoning; the real question is “What are the best witnesses at this specific point?”, and

generalizations simply do not answer that question. It is like deciding which football team wins the ballgame when the score is tied by asking which kicker has made the most field goals, instead of by actually scoring more points than the other team.

Third, this supposed harmonization doesn’t yield a tight harmony. Let’s compare the text of Matthew 17:21 to Mark 9:29. Mark wrote, τοῦτο τό γένος ἐν οὐδενὶ δύναται ἐξελθειν εἰ μὴ ἐν

προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ. (Regarding the

Alexandrian text’s non-inclusion of καὶ νηστείᾳ, see my

earlier analysis.) Metzger’s plea

that Mark 9:29 was transplanted into Matthew 17 is complicated by the distinct

lack of verbal similarity:

Matthew: τοῦτο δὲ τό γένος ούκ

ἐκπορεύεται εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ.

Mark: τοῦτο τό γένος ἐν οὐδενὶ δύναται ἐξελθειν εἰ μὴ ἐν προσευχῇ καὶ νηστείᾳ.

This

is not a verbatim harmonization – out

of 12 words (in Matthew 17:21), nine are identical – and Metzger’s comment that

“copyists frequently inserted material derived from another Gospel” fails to explain

why a scribe with Mark 9:29 in front of him would change 25% of its wording

when inserting it into the text of the Gospel of Matthew. It should also be noted that the kind of

harmonization Metzger referred to usually involved harmonization to

the text of Matthew in Mark and Luke, not the other way around (the harmonization

of Matthew 9:13 and Mark 2:17 to Luke 5:32

being a notable exception).

I

propose that an early Western scribe intentionally omitted the material we know

as Matthew 17:21 out of concern that readers might think that the ability of

the Son of God was limited depending on whether he fasted or not. (The same concern motivated the omission of καὶ νηστείᾳ in Mark 9:29.) This exclusion was

subsequently adopted by scribes in the Alexandrian transmission-line, which led

to the reading (or non-reading) in À B Q et

al.

Matthew 17:21 should be regarded as an authentic part of

the Gospel of Matthew. The oldest

evidence, the most geographically diverse evidence, and the vast majority of

evidence all point in favor of its inclusion.

The NIV, ESV, etc. should be corrected accordingly.

Thanks to Jonathan Borland for sharing his insightful research.