|

| Ethiopic MS 11, Image 7 (Gospel of John) |

In the fourth edition of The Text of the New Testament, on p. 322 (repeating what was on p. 226 of the first edition, written in 1964), Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman state, “A number of manuscripts of the Ethiopic version” do not contain Mark 16:9-20. (Full title: The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration). The late esteemed apologist Norman Geisler wrote that not only are verses 9-20 “are lacking in many of the oldest and most reliable manuscripts,” (see pp. 377-378 of The Big Book of Bible Difficulties, © 1992, a.k.a. When Critics Ask), but he also repeated the statement about Ethiopic MSS, writing, “These verses are lacking in many of the oldest and most reliable Greek manuscripts, as well as in important Old Latin, Syriac, Armenian, and Ethiopic manuscripts.” (Neither statement is altogether true , as we shall see shortly. Only two unmutilated Greek MSS do not support Mark 16:9-20, and only one undamaged Old Latin manuscript, and only one unmutilated Syriac MS. See here for information on GA 304 and GA 239.)

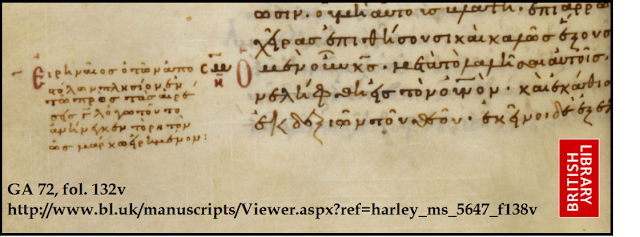

|

| Another example of Ge'ez script (from my collection) |

Dr. Geisler’s claim that Mark 16:9-20 is “lacking in many of the oldest and most reliable Greek manuscripts” is wrong – it’s lacking in only two ancient Greek manuscripts (Vaticanus and Sinaiticus). And the entire claim about Ethiopic manuscripts ending the Gospel of Mark at 16:8 is also wrong. In 1980, Bruce Metzger himself acknowledged that his earlier claim (in The Text of the New Testament, p. 226, 1964) was incorrect. (Not to detour from the subject of Ethiopic manuscripts, but on the same page, Metzger also wrote, erroneously, that Eusebius shows no knowledge of the existence of Mark 16:9-20. This was quietly altered in subsequent editions by replacing the name “Eusebius” with Ammonius – which is also incorrect as I explained in a recent post).

In 1980, in the scholarly journal New

Testament Tools and Studies, Metzger published an essay called “The

Gospel of St. Mark in Ethiopic Manuscripts.” In this essay he

demonstrated that in 1889 William Sanday had perpetuated errors made by two

other researchers (D. S. Margoliouth and A. C. Headlam) in a collation of

twelve Ethiopic manuscripts made by D. S. Margoliouth and edited by A. C. Headlam. As a result, a claim was spread to the effect

that “three Ethiopic manuscripts in the

But when Metzger personally checked the listed MSS, he discovered that “The three manuscripts which are said to omit verses 9 to 20 in reality contain the passage. Furthermore, an examination of the seven manuscripts disclosed that, instead of replacing the longer ending with the shorter ending, these witnesses actually contain both the shorter ending and the longer ending.” He also affirmed, after combining his own results with the research of William F. Macomber, S. J., that “Of the total of 194 (65 + 129) manuscripts, all but two (which are lectionaries) have Mark 16:9-20, while 131 manuscripts contain both the Shorter Ending and the Longer Ending.”

In other words, all of the commentators who have been saying that some Ethiopic MSS end Mark at 16:8 are wrong.

Some other points that Metzger mentioned in 1980 are worth noticing, to appreciate the weight of the Ethiopic version in general:

● The oldest dated Ethiopic MS that contains the Shorter Ending was made in 1343.

● The oldest undated Ethiopic MS that that contains the Shorter Ending between 16:8 and 16:9 was made in the 1200s.

● One Ethiopic MS at the Chester

Beatty Library (Ethiopic Manuscript 912), made in the 1700s, ends the Gospel of

Mark near the end of 16:8, but Metzger explains that “it is certain that the

manuscript in its present state is fragmentary and that originally it continued

with additional textual material.”

The value of the Ethiopic version

has increased since the Ethiopic

Garima Gospels were dated (via radiometric analysis) to no later than the

mid-600s (and I think the Garima Gospels was probably made a bit earlier, in the mid-500s). (And the Ethiopic version continues to be

given attention at the Hill

Museum and Manuscript Library, and new discoveries continue to be made.) Unfortunately this does not seem to have

elicited a desire to withdraw the erroneous claim that important Ethiopic

manuscript omit Mark 16:9-20 – a claim that was disseminated in academia since Tischendorf

and Warfield – and which was still disseminated in the third and fourth

editions of Metzger’s The Text of the New

Testament (see p. 275 of Bruce Metzger’s The

Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, 1992, and page 322 of the fourth edition. Yes; the fourth edition, co-edited with Bart

Ehrman, says two different things, depending on which page you’re reading.) and

which

can be read online right now at the Defending Inerrancy website, along with

other obsolete erroneous claims taken from the 1964 edition of Metzger’s book.

The evidence described by Metzger shows that all unmutilated Ethiopic MSS of Mark known to exist contain Mark 16:9-20. It also suggests that some time after the Gospel of Mark was translated into Ethiopic (with Mark 16:9-20 immediately following 16:8), the Shorter Ending intruded into the Ethiopic text-stream (probably from the Secondary Alexandrian transmission-stream represented in Mark 16 by 019 044 099 etc.) and was adapted as a liturgical flourish to conclude a lection-unit which would have otherwise concluded at the end of 16:8. (I suspect that at first the Shorter Ending – in its later form, with the variant “appeared to them” – was in the margin, like in Bohairic MS Huntington 17.)

Anyway: I am sure that Metzger and Nida etc. would

not want to go on spreading false information.

Of course authors cannot undo the damage after they die. So if you happen to find a book claiming that

“A number of manuscripts of the Ethiopic version do

not contain Mark 16:9-20,” the authors would no doubt thank you for writing in

the margin, in ink, “This is false. See

Metzger’s retraction in Tools & Studies X, 1980.” Because that number is ZERO.