Having seen that a scribal note at the

end of Luke 9:54 became extremely popular and eventually dominated over 99.5%

of extant manuscripts, let’s move along to the fascinating cluster of variants

in verses 55-56 – one of the most difficult variant-units in the New Testament. Metzger’s

six-line dismissal of the longer readings has been augmented in online studies

by several researchers including Robert

Clifton Robinson and the NET’s

annotator. Zooming in on verse 55

first, we see that the Textus Receptus, the Byzantine Textform, and the Majority

Text and quite a few MSS read (after αὐτοἷς) καὶ εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε οίου

πνεύματός ἐστε ὑμεις” and verse 56 begins with ὁ γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν

ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ σῶσαι. – that is (in the EOB New Testament) “You do not know of what kind of spirit you are. The Son of Man did not come

to destroy people’s lives but to save them.”

Weighing in for non-inclusion

are P45 P75 À A B C E G H L S V W D X Y Ω and

about 430 minuscules including 28 33 157 565 892 1424 etc. The Sinaitic Syriac

and the Sahidic version do not include the material. Cyprian supports the inclusion of "the Son of Man is not come to destroy men's lives, but to save them" (in Letter 58:2 - thanks to Demian Moscofian for this reference). Chrysostom supports the inclusion of εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε οίου

πνεύματός ἐστε ὑμεις and non-inclusion of ὁ

γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ σῶσαι. Epiphanius supports inclusion. Basil weighs in for non-inclusion.

Majuscules that support inclusion (with minor variations)

include D (although

D does not include ὑμεις at the end of v. 55 and 56a) Y M K U Γ Θ Λ Π, and the

1,300 minuscules that include the longer reading include f1 f13

124 180 205 597 700 1006 1243 1292 1505.

Willker noticed that 240 minuscules read ποίου instead of οίου (agreeing

with D), and that 33 minuscules have the first segment of verse 56 before the

last segment of verse 55. Latin support

for non-inclusion includes a, aur, b, c,

e, f, q, r1 and the Clementine and Wordsworth’s edition of the

Vulgate. Nestle’s Novum Testamentum Latine reads “Et conversus increpavit illos, dicens : Nescitis euius spiritus estis. Filius hominis non venit animas perdere, sed

salvare.” I have not verified the

claim that Codex

Fuldensis supports non-inclusion. The

Curetonian Syriac, the Peshitta, and Harklean Syriac support inclusion and so

do the Armenian and Gothic versions. Ambrose

and Ambrosiaster both support the longer reading.

Majuscules that support inclusion (with minor variations)

include D (although

D does not include ὑμεις at the end of v. 55 and 56a) Y M K U Γ Θ Λ Π, and the

1,300 minuscules that include the longer reading include f1 f13

124 180 205 597 700 1006 1243 1292 1505.

Willker noticed that 240 minuscules read ποίου instead of οίου (agreeing

with D), and that 33 minuscules have the first segment of verse 56 before the

last segment of verse 55. Latin support

for non-inclusion includes a, aur, b, c,

e, f, q, r1 and the Clementine and Wordsworth’s edition of the

Vulgate. Nestle’s Novum Testamentum Latine reads “Et conversus increpavit illos, dicens : Nescitis euius spiritus estis. Filius hominis non venit animas perdere, sed

salvare.” I have not verified the

claim that Codex

Fuldensis supports non-inclusion. The

Curetonian Syriac, the Peshitta, and Harklean Syriac support inclusion and so

do the Armenian and Gothic versions. Ambrose

and Ambrosiaster both support the longer reading.

(GA 579 has a unique expansion which I will ignore here.)

Early readers might have wondered know what Jesus said when he rebuked James

and John. But would they be willing to

invent a response from Jesus and present it as if it originated with

Jesus? Is it likely that a scribe would

add this sentence knowing that it was not originally part of Luke’s Gospel?

On

the other hand, if Luke wrote καὶ εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε οίου πνεύματός ἐστε

ὑμεις ὁ γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν

ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ σῶσαι, what possible motive would any scribe have

to remove these words? Luke preserved

Jesus’ saying (in 19:10) that the Son of Man came to seek and to save the lost

– so why add a similar statement here?

A

very bad case of parablepsis could account for the loss of καὶ εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε

οίου πνεύματός ἐστε ὑμεις ὁ γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ

ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ σῶσαι if a scribe’s line of

sight drifted from the καὶ after αὐτοῖς to the καὶ before ἐπορεύθησαν. However this seems unlikely for several

reasons. First, due to the large amount

of lost material. Second, because a

proof-reader would almost certainly correct the omission. Third, because the attestation for

non-inclusion are from Alexandrian (P75 À B

Sahidic),

Western (Old Latin a b c r1

), and Byzantine (A S Ω 1424) transmission-lines.

Let’s

take a closer look at a few of Chrysostom’s utilizations of Luke 9:55-56. Near the end of Homily on Matthew 29 he

cited 9:55b plainly. Ini his 51st Homily on John he

utilized 9:55b again. And he did so again in Homily on First Corinthians

33 when commenting on I Cor. 13:5, writing, “Wherefore

also when the disciples besought that fire might come down, even as in

the case of Elijah, ‘You know not,’ says Christ, ‘what manner of spirit you are of.’”

We

are looking at two variants here, not just one:

(1) the addition of καὶ εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε οίου πνεύματός ἐστε ὑμεις and (2)

the inclusion of ὁ γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ

σῶσαι. We are also looking at several

strata in the transmission of the text.

I suspect we are dealing with a

phenomenon involving marginalia in the autograph. Whether the marginalia was added by Luke, or

by a later scribe, is very difficult to determine. Imagine the main text of verses 55-56 looking

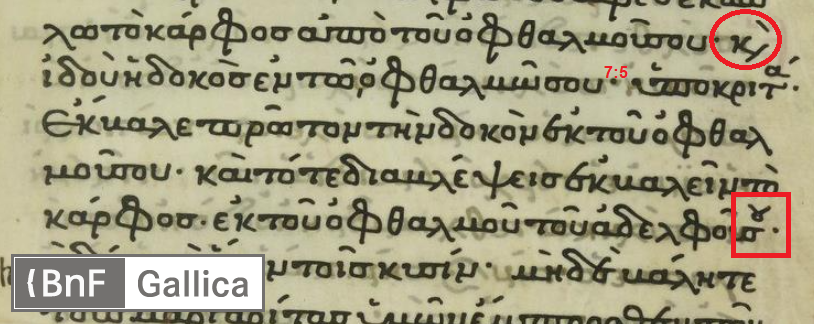

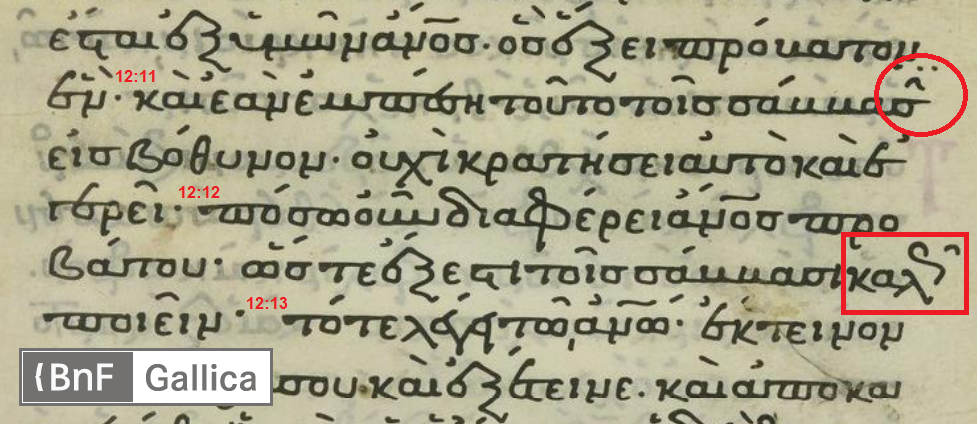

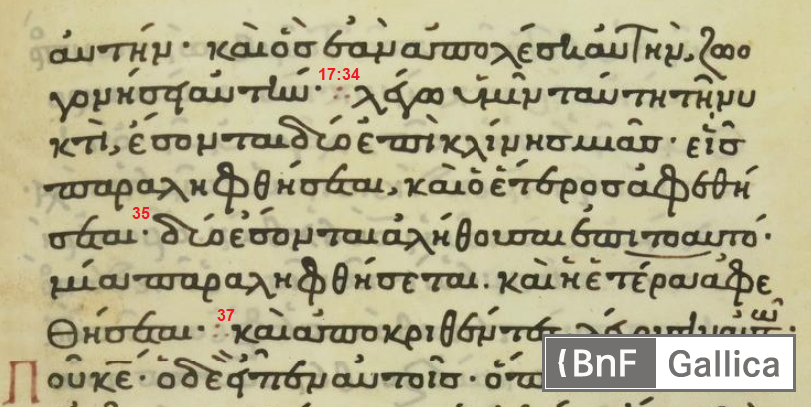

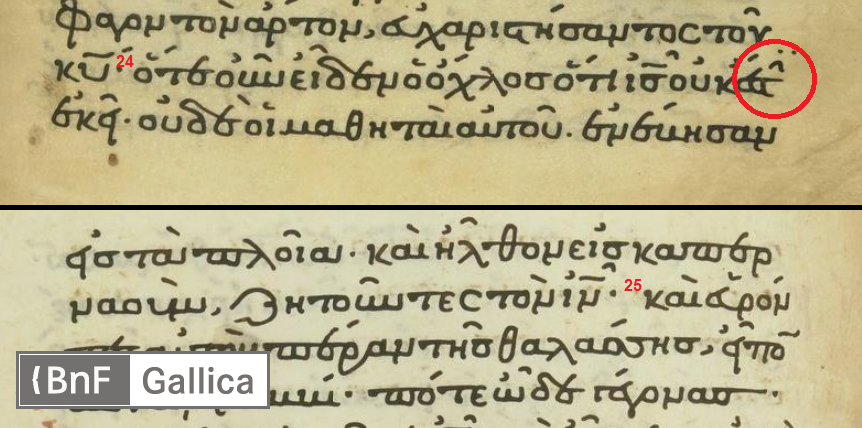

like it does in Codex S (028). Then

picture καὶ εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε οίου πνεύματός ἐστε ὑμεις in the margin to the

left, and ὁ γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ σῶσαι

in the margin to the right. Scribes coming

to this could interpret it in different ways.

To encapusulate the hypothetical history of the text at this point, I

will name alphabetically the scribes who treated it differently:

Alex and Bill perpetuate only

the main text, thinking that the marginalia is all secondary and non-Lukan.

Cecil perpetuates the main text

and includes all the marginalia as the text in the copy he produces.

Dexter perpetuates the main text and

includes 55b in the main text of the

copy he produces.

Later, using exemplar based on the

ones made by Bill and Cecil, Edward made a copy resembling most Byzantine MSS,

with 55b and 56a indiscernible from the rest of the text.

Fred similarly made a copy including

55b and 56a, but in a different order.

How should modern English versions

handle this? I would be content with

what we see in the New American Standard Bible (1995), but with brackets only

around 56b: “But He turned

and rebuked them, and said, “You do not know what kind of spirit you are of [for

the Son of Man did not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.”] And

they went on to another village.” Let’s

see an array of different treatments:

Modern English versions have handled this variants in

a variety of ways:

NIV: But Jesus

turned and rebuked them. Then he and his disciples

went to another village. (no footnote)

NLT: But Jesus

turned and rebuked them.a

The footnote reads: “Some

manuscripts add an expanded conclusion to verse 55 and an additional sentence

in verse 56: And he said, “You don’t realize what your hearts are like. 56 For

the Son of Man has not come to destroy people’s lives, but to save them.””

ESV: But he turned

and rebuked them.a The

footnote reads: “Luke 9:55

But he turned and rebuked them, “You don’t know of what kind of spirit you are. For the Son of Man didn’t come

to destroy men’s lives, but to save them.”

EHV: But he turned and rebuked them. “You don’t

know what kind of spirit is influencing you.

For the Son of Man did not come to destroy people’s souls, but to save

them.”a Then they went to another

village. The footnote reads “Luke 9:56

The Message hyper-paraphrase:

“Jesus turned on them: “Of

course not!” And they traveled on to another village.”

Christian Standard Bible: “and they went

to another village.” (Footnote: Other mss add and said, “You don’t know what kind of spirit you belong to. 56 For the Son of Man did not come to destroy people’s lives but to save them,”)

In

conclusion, with the present state of evidence, the best option is to include καὶ

εἶπεν οὐκ οἴδατε οίου πνεύματός ἐστε ὑμεις in the text and ὁ γὰρ υἱὸς τοῦ

ἀνθρώπου οὐκ ῆλθεν ψυχὰς ἀνθρώπων ἀπολέσαι άλλὰ σῶσαι in a footnote.