Guess which

manuscript has more corruptions in Luke 2:1-21:

Codex Bezae (for which researcher D. C. Parker has assigned a

production-date around 400), or the

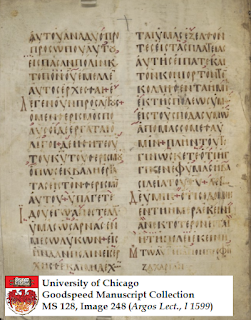

Georgius Gospels (a minuscule manuscript

from the 1200’s)? We could

use the

Byzantine Textform compiled by Maurice Robinson and William Pierpont as

the basis for this comparison. But

instead, let’s compare each manuscript’s text of Luke 2:1-21 – Luke’s narrative

about the birth of Christ – to the Nestle-Aland compilation.

2:1 – 2266 has εξηλθε instead of εξηλθεν. (-1) ■

2:2 – 2266 has η

after αυτη. (+1) ▲

2:3 – 2266 has ιδιαν

instead of εαυτου. (-6 and +5) ▲

2:4 – 2266 has Ναζαρετ

instead of Ναζαρεθ. (-1 and +1) ▲

2:5 – 2266 has μεμνηστευμενη instead of εμνηστευμενη. (+1) ▲

2:5 – 2266 has the word γϋναικι

before ουση. (+7) ▲

2:5 – 226 has εγγυω

instead of εγκυω. (-1 and +1)

2:7 – 2266 has τη

before φατνη. (+2) ▲

2:9 – 2266 has ιδου

after the first και. (+4) ▲

2:10 – 2266 has

θοβηστε instead of θοβειστε. (+1 and -2)

2:11 – 2266 has

εστι instead of εστιν. (-1) ■

2:12 – 2266 does

not have και before κειμενον. (-3) ▲

2:15 – 2266 has οι ανοι (the contraction of ανθρωποι) after οι αγγελοι και. (+10) ▲

2:15 – 2266 has

ειπον instead of ελαλουν. (-7 and +5) ▲

2:16 – 2266 has

ηλθον instead of ηλθαν. (-1 and +1) ▲

2:16 – 2266 has

ανευρον instead of ανευραν. (-1 and +1) ▲

2:17 – 2266 has διεγνωρισαν instead of εγνωρισαν. (+2) ▲

In addition, 2266 contracts the following words which appear

at the ends of lines:

2:4 – 2266 has Γαλιλ′ instead of Γαλιλαιας. (-4)

2:11 – 2266 has

πολ′ instead of πολει. (-2)

2:12 – 2266 has

κειμεν′ nstead of κειμενον. (-2)

2:21 – 2266 has επλησθησ′

instead of επλησθησαν. (-2)

In a strict letter-by-letter count, without considering

contractions of nomina sacra , abbreviations of και, and the

contractions at the ends of lines, in 2266, 22 letters of the original text

have been lost, and 43 non-original letters have been introduced. Thus, whether via addition or subtraction,

the text of 2266 differs from the text of NA27 by 65 letters.

Aside from spelling-variants, these 65 letters’ worth of

difference between the text of Luke 2:1-21 in the Georgius Gospels and in the Nestle-Aland

compilation consist mainly of these seven variants:

● the

interchange between ιδιαν and εαυτου in verse 3,

● the

introduction of γϋναικι in verse 5,

● the

introduction of ιδου in verse 9,

● the

absence of και in verse 12,

● the

introduction of οι ανθρωποι in verse 15, and

● the

interchange between ειπον and ελαλουν in verse 15.

Now let’s look at the text of Luke 2:1-21 in Codex Bezae.

. . . Are you sure you’re ready? Take a deep breath.

2:1 – D moves εγενετο to follow αυτη instead of πρωτη.

2:3 – D has πατριδα

instead of πολιν. (+6, -4)

2:4 – D has γην

instead of την. (-1)

2:4 – D has Ιουδα instead of Ιουδαιαν. (-3)

2:4 – D has Δαυειδ

instead of Δαυιδ. (+1)

2:4 – D has καλειτε

instead of καλειται. (+1, -2)

2:4-5 – D moves απογραφεσθαι συν Μαρια τη εμνηστευμενη αυτω

ουση ενκυω to immediately follow Βηθεεμ.

Within the transposed portion, D has απογραφεσθαι instead of απογραφασθαι,

and Μαρια instead of Μαριαμ, and ενκυω instead of εγκυω. (+2, -3)

2:5 – D has Δαυειδ

instead of Δαυιδ. (+1)

2:6 – D has ως δε παρεγεινοντο instead of εγενετο δε εν τω

ειναι αυτους εκει. (+14, -26)

2:6 – D has ετλησθησαν

instead of επλησθησαν. (+1, -1)

2:8 – D has Ποιμενες δε instead of Και ποιμενες. (+2, -3)

2:8 – D has χαρα

ταυτη instead of χωρα τη αυτη. (+1, -2)

2:8 – D has τας before φυλακας. (+3)

2:9 – D has ιδου

after the first και. (+4)

2:9 – D does not have κυριου

after δοξα. (-6)

2:10 – D has υμειν instead of υμιν. (+1)

2:10 – D has και before παντι. (+3)

2:11 – D has υμειν instead of υμιν. (+1)

2:11 – D has Δαυειδ instead of Δαυιδ. (+1)

2:12 – D has υμειν instead of υμιν. (+1)

2:12 – D has εστω after σημειον. (+4)

2:12 – D does not

have και κειμενον. (-11)

2:13 – D has

στρατειας instead of στρατιας. (+1)

2:13 – D has

ουρανου instead of ουρανιου. (-1)

2:13 – D has αιτουντων instead of αινουντων. (+1, -1)

2:15 – D moves οι

αγγελοι to follow απηλθον.

2:15 – D has και

οι ανθρωποι before οι ποιμενες.

(+10)

2:15 – D has

ειπον instead of ελαλουν. (+3, -5)

2:15 – D has

γεγονως instead of γεγονος. (+1, -1)

2:15 – D has ημειν instead of ημιν. (+1)

2:16 – D has ελθον instead of ελθαν. (+1, -1)

2:16 – D has σπευδοντες instead of σπευσαντες.

(+2, -2)

2:16 – D has

ευρον instead of ανευραν. (+1, -3)

2:16 – D does not

have τε before Μαριαμ. (-2)

2:16 – D has

Μαριαν instead of Μαριαμ. (+1, -1)

2:17 – D does not

have τουτου at the end of the verse.

(-6)

2:18 – D has ακουοντες instead of ακουσαντες.

(+1, -2)

2:18 – D has

εθαυμαζον instead of εθαυμαζαν. (+1, -1)

2:19 – D has

Μαρια instead of Μαριαμ. (-1)

2:19 – D has a

transposition: συνετηρει παντα instead

of παντα συνετηρει.

2:19 – D has συνβαλλουσα instead of συμβαλλουσα. (+1, -1)

2:20 – D has ιδον

instead of ειδον. (-1)

2:21 – D has συνετελεσθησαν instead of επλησθησαν. (+6, -1)

2:21 – D has αι

before ημεραι. (+2)

2:21 – D has αι

before οκτω. (+2)

2:21 – D has το

παιδιον instead of αυτον. (+9, -5)

2:21 – D has

ωνομασθη instead of και εκληθη. (+8, -9)

2:21 – D has συνλημφθηναι instead of συλλημφθηναι. (+1, -1)

2:21 – D does not

have τη before κοιλια. (-2)

2:21 – D has

μητρος after κοιλια. (+6)

That’s 106 additions of non-original letters, and 109

subtractions of original letters.

Whether by addition or subtraction, the text of Luke 2:1-21 in Codex Bezae

differs from the text of NA27 by 215 letters (without considering the

transpositions). For comparison: compared to NA27, the corruptions in 2266

amount to 65 letters (or 75, if we toss in the letters lost in end-of-line

contractions), and the corruptions in D amount to 215 letters.

Setting aside spelling-variations and transpositions, these 215 letters’ worth of difference between the text of D and the

Nestle-Aland compilation consist mainly of these 23 variants:

● 2:3 – D has πατριδα

instead of πολιν. (+6, -4)

● 2:4 – D has γην

instead of την. (-1)

● 2:4 – D has Ιουδα instead of Ιουδαιαν. (-3)

● 2:6 – D has ως δε παρεγεινοντο instead of εγενετο δε εν τω

ειναι αυτους εκει. (+14, -26)

● 2:8 – D has χαρα

ταυτη instead of χωρα τη αυτη. (+1, -2)

● 2:8 – D has τας before φυλακας. (+3)

● 2:9 – D has ιδου

after the first και. (+4)

● 2:9 – D does not have κυριου

after δοξα. (-6)

● 2:10 – D has και before παντι. (+3)

● 2:12 – D has εστω after σημειον. (+4)

● 2:12 – D does

not have και κειμενον. (-11)

● 2:15 – D has και

οι ανθρωποι before οι ποιμενες.

(+13)

● 2:15 – D has

ειπον instead of ελαλουν. (+3, -5)

● 2:16 – D has

ευρον instead of ανευραν. (+1, -3)

● 2:16 – D does

not have τε before Μαριαμ. (-2)

● 2:17 – D does

not have τουτου at the end of the verse.

(-6)

● 2:21 – D has συνετελεσθησαν instead of επλησθησαν. (+6, -1)

● 2:21 – D has αι

before ημεραι. (+2)

● 2:21 – D has αι

before οκτω. (+2)

● 2:21 – D has το

παιδιον instead of αυτον. (+9, -5)

● 2:21 – D has

ωνομασθη instead of και εκληθη. (+8, -9)

● 2:21 – D does

not have τη before κοιλια. (-2)

● 2:21 – D has

μητρος after κοιλια. (+6)

Now let’s revisit those seven variants in 2266 that

constituted its main disagreements with the NA27 compilation. Do you think they might be late readings that

somehow got attached to the text in the Middle Ages, like snowflakes attaching

themselves to a snowball as it rolls down a hill? Let’s take a look at the allies of 2266, and

see how old these readings are.

● 2:3 – ιδιαν instead of εαυτου: supported by Codex A.

● 2:5 – γϋναικι:

supported by Codex A.

● 2:9 – ιδου: supported

by Codex A.

● 2:12 - και is

absent: supported by Codex A.

●

2:14 – ευδοκια: supported by L, Eusebius, Ambrose, Jerome,

and Chrysostom (among others)

● 2:15 – οι

ανθρωποι: supported by Codex A.

● 2:15: ειπον: supported by Codex A.

Thus, compared to the text of Codex A, we see practically no

“snowball effect” in the transmission of the text of Luke 2:1-21 in 2266. If these readings are accretions, they are

early ones. Furthermore, compared to the

text of Codex D, 2266 has by far the more accurate text. Using the Byzantine Text as the basis of

comparison, 2266 has almost no deviations.

Using the Nestle-Aland compilation as the basis of comparison, 2266’s

text has lost 22 original letters and added 43 non-original letters – mostly in

agreement with Codex A. Meanwhile the

text of Codex D has lost 109 original letters, and has accrued 106 non-original

letters (and also contains several transpositions).

Again: the Georgius Gospels is the clear winner. In Luke 2:1-21, using NA27 as the basis of comparison, the Georgius Gospels has only one-third as much corruption as Codex Bezae contains.

[Readers are invited to double-check the comparisons and arithmetic.]