Two textual issues in Acts 20:28 have impacted translations

of the verse: First: did Luke refer to the church as the “

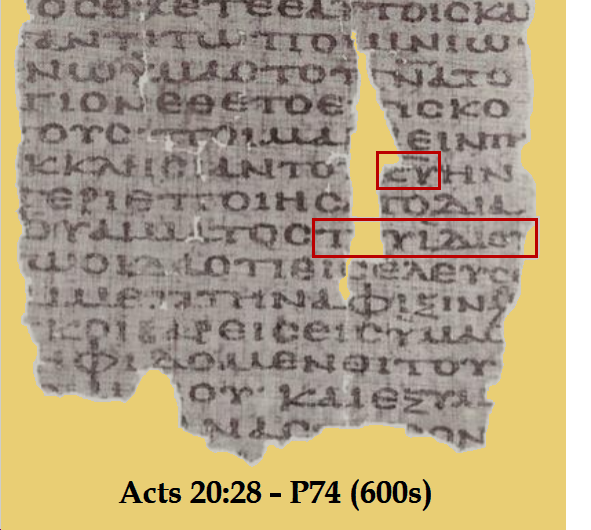

Let’s review the external evidence:

Greek Support for ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ θεοῦ includes ﬡ B 056 614

1175 1611 104 2147 1505 Byz, Lectionary 60, l592,

l598, l603, l1021, and l1439. Versional support is provided by the Vulgate,

the Peshitta, the Harklean Syriac, the Georgian version, and itar, c, dem,

ph, ro, w and a Bohairic copy.

Patristic support for ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ θεοῦ is supplied by Athanasius,

Basil, Epiphanius, Chrysostom, Cyril, and Ambrose.

Greek

support for ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ κυρίου καί θεοῦ includes H L P C3 049 1 69

88 226 323 330 440 618 927 1241 1245 1270 1828 1854 2492 and most

lectionaries. Versional support is

limited to a Slavic lectionary copy.

(In

addition, Swanson recorded GA 1837’s ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ κυ ιυ καί θῦ.)

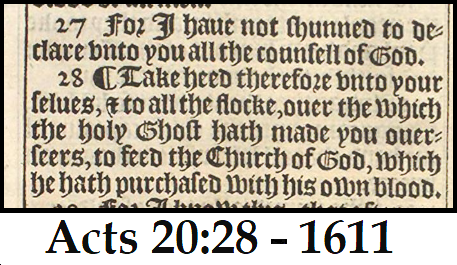

The KJV,

reflecting the Textus Receptus, reads

“Take heed therefore unto

yourselves, and to all the flock, over the which the Holy Ghost hath made you

overseers, to feed the

Similarly, the Christian Standard Bible reads “shepherd the

The World English Bible, following the

Byzantine Text, reads, “Take heed, therefore, to yourselves, and to all the

flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to shepherd the

assembly of the Lord and God which

he purchased with his own blood.”

Modern versions render Acts 20:28 in

quite diverse ways: usually the

base-text τοῦ θεοῦ is followed, not only in the English

Standard Version, NIV, EHV and CSB but also in the NET, RSV, NRSV, CEB, and

CEV.

Likewise the NRSV (including the compromised Updated

Edition) have Paul tell the Ephesian elders to “shepherd the

The Lexham English Bible likewise reads, “shepherd

the

English

versions which end Acts 20:28 with a clear reference to the blood of God’s Son

– even though the Greek equivalent of the

word “son” is not in the base-text – include the NWT, NET, RSV, NRSV, CEV,

Lexham, GNT, Mounce, The Voice,

and CEB.

In 1881 Hort wrote over three columns

of his Notes on Select Readings about

Acts 20:28 and concluded that “It is by no means impossible that ΥΙΟΥ dropped

out after ΤΟΥΙΔΙΟΥ at some very early transcription affecting all existing

documents. Its insertion leaves the

whole passage free from difficulty of any kind.” Metzger mentioned that Hort’s proposal is not

necessary – but no less than nine modern English versions appear to be

conformed to Hort’s proposed emendation!

Metzger dismissed the majority reading as “obviously conflate.” The Byzantine reading τοῦ κυρίου καί θεοῦ may account for both of the longer readings, however, if early scribes committed parablepsis, skipping from the –ou of κυρίου to the –ου of θεοῦ (producing ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ κυρίου), and some subsequently substituting θεοῦ in place of κυρίου, resisting the idea of God having blood.

The

Tyndale House Greek New Testament reads “ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ κυρίου” and concludes

with “αἵματος τοῦ ἰδίου.” Holmes’

SBL-GNT reads “ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ θεοῦ” and concludes the verse with “αἵματος τοῦ

ἰδίου.”

It

may be worthwhile to consider the thoughts of some who have approached the

textual issue from a pastoral perspective – for example Bob Luginbill, Sam Shamoun,

and the La

Vista Church of Christ (near

Considering that the longer reading’s earliest appearance is relatively late, and that ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ θεοῦ is supported by the Peshitta, the Vulgate, Chrysostom and Athanasius, ἐκκλησίαν τοῦ θεοῦ should be adopted, being early, geographically widely supported, and attested in multiple transmission-lines. GA 1739’s text may be adopted for the entire verse.

English readers should be aware that at least eight modern versions essentially echo a conjectural emendation in this verse.