I am pleased to present and review a relatively new English New Testament: the Eastern/Greek Orthodox New Testament, also known as the New Testament portion of the Eastern Orthodox Bible (abbreviated from here on as “EOB-NT”), which was initially published in 2013.

|

| Laurent Cleenewerck |

“The EOB New Testament,” says its online

presentation at Amazon, “is a new translation of the official Greek Orthodox

text called the Patriarchal Text of 1904.”

It goes on to say that the EOB-NT is “a fresh and accessible translation

created within the Orthodox community.”

Its editor is identified as Laurent Cleenewerck. Presbyter Cleenewerck currently

serves as the rector of Saint Innocent

Orthodox Christian Church in

New

English translations are not uncommon nowadays:

the past 50 years have seen the premiere of the NIV 1984 (now

discontinued), NASB

(updated in 1995), ESV

(updated in 2016), HCSB, CSB (2017), CEB, CEV,

NLT, TNIV (now

discontinued), NIV 2011, NRSVue, and so

forth. Meanwhile, many advocates of the

KJV have resisted these translations, arguing (among other things) that they

either omit a significant number of verses and phrases, or relegate them to the

footnotes.

The

EOB New Testament poses a challenge to such objections. In its extensive introduction

(p. viii), one finds a statement that the purpose of its Greek base-text “is not to offer an always

speculative reconstruction of the original autographs but to provide a uniform

ecclesiastical text which is a reliable and accurate witness to the truth of

the Christian faith.”

Because it is

based on the 1904 Patriarchal Text, the EOB-NT includes all these verses and

phrases (with footnotes mentioning the reading of the CT – Critical Text – in

each case): Matthew 6:13b, Matthew 12:47, Matthew 13:14 “spoken

of by Daniel the prophet,” Matthew 16:2b-3,

Matthew 17:21, Matthew 18:11, Matthew 20:16b,

Matthew 23:14 (as 23:13), Mark 6:11b,

Mark 7:16, Mark 9:29 “and fasting,” Mark 9:44, Mark 9:46, Mark 11:26, Mark

14:24 “new,” Mark 15:28, Mark 16:9-20, Luke 4:8, Luke 9:55-56, Luke 11:2b, Luke 11:4b, Luke 17:36, Luke 22:43-44,

Luke 23:17, Luke 23:34a, Luke 24:12, Luke 24:40, Luke 24:42b, Luke 24:51b, John

3:13, “who is in heaven,” John 5:3-4, John 7:53-8:11, Acts 8:37, Acts 9:5-6, Acts

13:42, Acts 15:34, Acts 23:9b, Acts 24:6-8, Acts 28:29, Romans 1:16, “of Christ,”

Romans 16:24, and First John 5:7-8.

Although the EOB-NT

contains the Johannine Comma in First John, its footnote states explicitly that

this reading is supported by “a few recent Greek manuscripts,” and that “This passage

is undoubtedly an interpolation or later theological comment seemingly of

Spanish-Latin origin.”

Unlike the NKJV and MEV, the EOB-NT

rejects many of the readings in the Textus

Receptus (and KJV) which are not supported by the Byzantine Text. It is similar to the World English Bible

(which makes sense considering that, as its introduction says, the EOB-NT “began

as a revision of the WEB”). Here are some

examples of readings in the Gospel of Matthew in the EOB-NT that are different

from the KJV due to different readings in their base-texts:

3:8 – “fruit” (not “fruits”)

5:47

– “friends (not “brethren)

7:2

– does not have “again”

8:15

– “him” (not “them”)

9:36

– “weary” (not “fainted”)

12:35

– does not have “of the heart”

18:19

– “Again, amen” (not just “Again”)

18:29

– does not have “all”

20:22

– “or” (not “and”)

20:26

– “shall be (not “let him be”)

21:1

– “Bethsphage” (not “Bethphage”)

26:26

– gave thanks for it” (not “blessed it”)

27:35

– does not have “that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophet,

They parted my garments among them, and upon my vesture did they cast lots”

27:41

– includes “and the Pharisees”

The

influence of a better and broader array of evidence manifests itself in many

other passages. Some samples:

● Luke 7:31 does not begin with

“And the Lord said,”

● John 1:28 refers to Bethany (not

Bethabara),

● Acts 9:5 does not include “It is

hard for thee to kick against the pricks,”

● Acts 9:6 does not include “And he

trembling and astonished said, ‘Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?’ And the

Lord said unto him,”

● Ephesians 3:9 reads

“dispensation,”

● Philippians 4:3 begins with “Yes”

(not “And”)

● Colossians 1:6 includes “and

growing,”

● Colossians 1:14 does not include

“through his blood,”

● James 4:12 includes “and judge,”

● First Peter 2:2 includes “in

salvation.”

● Jude verse 4 refers to “our only

Master and Lord Jesus Christ,”

● Revelation 6:12 refers to the

“whole moon,”

● Revelation 8:13 refers to “an

eagle,” and

● Revelation 22:20 refers to the

“tree of life” (not “book of life” as in the KJV).

At

all these points (and many more) the EOB-NT’s base-text has preserved the

original text better than the Textus

Receptus.

To illustrate the EOB-NT's translation-technique, here

are three sample extracts from the EOB-NT:

● JOHN 1:12: “But as many as received him, to them he gave

the ability to become God’s children, to those who believe in his Name.”

● FIRST TIMOTHY 3:2: “The overseer must be irreproachable, a

husband of one wife, self-controlled, sensible, modest, hospitable and a good

teacher.”

● TITUS 3:4-5: “But when the kindness of God our Savior and

his love toward mankind appeared (not by works of righteousness which we did

ourselves, but according to his mercy), he saved us through the washing of

regeneration and renewing of the Holy Spirit.”

The

translation-technique of the EOB-NT comes very close to Bruce Metzger’s ideal

of “as literal as possible, as free as

necessary.” Monetary terms and

ancient measurement-units are not converted into their modern equivalents; instead,

footnotes explain the ancient terms via modern counterparts. The most unusual rendering is perhaps found

in Philippians 4:3, where the Greek word that is often rendered “yokefellow” or

“fellow-worker” is rendered in the EOB-NT as a proper name, Syzygus – with a

footnote conveying that this rendering is not airtight.

Extensive

quotations from the Old Testament are italicized.

Instead

of resorting to headings that interrupt the text, all of the EOB-NT’s headings

are in the side-margin, in italicized red print.

The

myriad footnotes in the EOB-NT mention very many textual variants in the Textus Receptus, the Majority Text, and

the Critical Text – far more than

the footnotes in the ESV and NIV and CSB – almost enough to give 100%

validation to the introduction’s claim that “All significant variants between

PT/MT/TR and CT have been studied and footnoted to provide variant readings.” Even some of Codex Bezae’s very unusual

readings have found a home in the EOB-NT’s footnotes, such as at Matthew 20:28,

Luke 22:19, 24:3, etc. – but not in the book of Acts.

Many

footnotes point out passages where a New Testament author’s citation of an Old

Testament passage agrees with the Septuagint.

Most of the footnotes are brief, but some come close to

commentary-summarizations; for instance, the footnotes for John 1:1-2, John

8:58, and Second Thessalonians 2:7 seem too prolix.

Footnote-readers will encounter occasional Greek words. And, unlike the writers of the footnotes in other English New Testaments, the EOB-NT’s footnote-writer was not afraid to mention patristic writers such as Irenaeus, Clement, Hippolytus, Origen, Epiphanius, Jerome, Basil, Hilary, Gregory of Nyssa, Cyril of Alexandria, and Theodoret. It is highly recommended that readers carefully absorb the Introduction to the EOB-NT and the prefatory Abbreviations and Codes (which identifies, among other things, the abbreviations for several English translations and 21 witnesses (mainly Greek manuscripts). However, that will not help the typical American reader to whom patristic authors are, sadly, a complete mystery. Such readers will just have to learn!

I suspect that the EOB-NT embodies the kind of revision of the traditional New Testament text that John Burgon wished for in the late 1800s – avoiding the Egypt-centric compilation that is currently presented as the text of “reasonable eclecticism” (in real life, it is 99% Alexandrian), and which is the basis of the New Testament in the ESV, NIV, CSB, NASB, NRSV, and NLT. The EOB-NT stands apart from these versions and is superior to them all.

This

is not to say that the EOB-NT is flawless.

Some of the readings in its base-text are not original. For instance, Matthew 25:13 in the EOB-NT

concludes with “that the Son of Man is coming,” which surely originated in the

Byzantine Text for the purpose of wrapping up a lection. But as far as I can tell, these accretions

are, one and all, quite benign, and they tend to clarify the meaning of the

passage in which they occur, just as the NIV routinely inserts a proper name where

there is no proper name in its base-text.

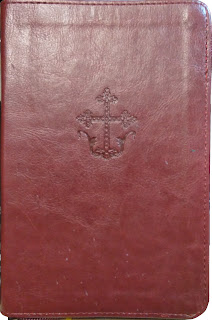

Its

burgundy leather cover has two ribbons, yellow and red. A zipper protects the pages (but also

prevents them from laying flat). The

print is small; some readers may need a magnifying-glass. There are two columns of text on each page.

The

text is formatted into logical paragraphs.

An

unfortunate formatting-error has survived in Matthew 27:31: the words “Simon of

As one handles the EOB-NT Portable Edition, one may feel as if a New Testament manuscript is being held. Each Gospel is preceded by a full-page illustration, and illustrations – more like icons – also appear before First Corinthians, and after Revelation. Each book of the New Testament, large or small, is introduced with an artistic, uncomplicated red headpiece, and the book-title in artistic red lettering. Chapter-numbers and superscripted verse-numbers are red. Footnote-numbers, in black, are also superscripted.

The

text is supplemented by useful colorful maps that deserve special mention. They depict the Roman Empire, Jesus’ Ministry

in Galilee, Jesus’ Journeys to Jerusalem, The Jewish Diaspora at Pentecost, Paul’s

Early Travels, Paul’s Third Missionary Journey, Paul’s Trip to Rome, The

Ministry of Peter and Philip, the Spread of Christianity During the 1st

and 2nd Centuries A.D., and Early Christian Communities, followed by

an icon of the Harrowing of Hell with Romans 8:31-34.

More

information about the EOB-NT Portable Edition can be found in the video-reviews

by Orthodox Review

and R. Grant Jones

and Biblical Studies and

Reviews.

23 comments:

Matthew 29:31 ???

Now that’s a chapter that I’m not aware of! 😁

John,

Touche! It's repaired now; thanks!

JSJ

I'm thinking that we now have very good representatives of the manuscripts used by the church in the east and the west. The Douay–Rheims Bible is pretty close to the manuscript Jerome had for his commentaries on the New Testament and I bet that the EOB will follow very closely Chrysostom's Greek text. We will have to wait now for a good translation in English of the text available to the church in Egypt. The ESV (or the NASB-95) may be an approximation, but not yet a good representative of the texts we find Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria using in their writings and commentaries.

The design seems quite nice (although I do prefer single columns). This would be awesome with the Greek text, and no zipper.

I had to cut a ribbon (cut both then)since it got stuck in the zipper! The large paperback has the Mat 27 headings properly formatted. But they are not in the margin but are rather bold in text headings.

does that mean that all those other translations were done by the DirtyWerck clan?

Hi Dr Sapp. Thanks for your work. I have a scoefield kjv Bible, and I dislike and distrust and therefore ignore the many comments. Ive read about a quarter of it. What’s a good starting Bible for someone well educated who just wants to read it (i mostly get my analysis and exegesis from commentators elsewhere, esp podcasts and videos)? Is it the eob? Or is that a good second Bible? From a few years ago, I thought you had a post about this question but couldnt find it. I guess Id like to go with more modern English than kjv but will end-up going to kjv on occasion. (Frankly, is not too important but I wouldnt mind one without verse numbers, but is hard to find and all I found also has no paragraph or any other breaks and those mustve been in the originals.)

Hi Dr Sapp. Thanks for your work. I have a scoefield kjv Bible, and I dislike and distrust and therefore ignore the many comments. Ive read about a quarter of it. What’s a good starting Bible for someone well educated who just wants to read it (i mostly get my analysis and exegesis from commentators elsewhere, esp podcasts and videos)?

Is it the eob? Or is that a good second Bible? From a few years ago, I thought you had a post about this question but couldnt find it. I guess Id like to go with more modern English than kjv but will end-up going to kjv on occasion. (Frankly, is not too important but I wouldnt mind one without verse numbers, but is hard to find, and the ones Ive seen also have no paragraph or any other breaks; such breaks must’ve been in the ancient Bibles, right?)

Dunno if your name or your comment is funnier

But regarding the New Testament, they all come from the same source right? So isn’t the ultimate job to take the three and integrate/reconcile them into a final version? (The three you just mentioned, jerome, chrysostom, and egypt’s). ie Why do we have two branches around?

Im sure that’s a basic question, but Im new to this. And once in a blue moon such a person says something basic but useful (plus Im just legit curious)

Hi Display Name, I will comment on your question that was directed to me. That's right! There is only one source of scriptures, but when you read the church fathers, you soon realize that there are variations in their texts. Minor variations in the word of God is a historical fact! You can read Chrysostom's commentary on the gospel of John and compare with Cyril's and you will realize that there are variations in their texts. Chrysostom's text is byzantine and tends to be closer to the EOB, because that was the form of the text that was used by the Greek speaking church in the East. Cyril's MSS is Alexandrian and will be closer to the critical text, because that was the form of the text that was available to the Church in Egypt. The third major branch is represented by the Latin fathers like Augustine and Jerome. Their text will tend to be closer to the DRB. The business of textual criticism is to compare those texts from those major branches and come to a conclusion as to what textual variant is the original. I hope that helps!

Thanks very much for the explanation. Very interesting.

You’re certainly welcome to comment on my other question; is already a lot but would also be greatly appreciated (if not even more so). Certainly my preference is toward matching original texts, but can’t have it all and there are undoubtedly other considerations for a relatively new believer (about two years, with MUCH study of exegesis but a paucity of simply reading the Bible itself, which I am ready to correct). Thanks again and God bless you very much so in Christ. 🙏🏻✝️

I still sortve wonder why all Bible versions come out intentionally close to one of the three branches rather than trying to use all three to work-out the best estimate of the originals. I guess one explanation is that a version IS trying to get to the original, but the translators/editors believe the branch near their version is the branch which is closest to the originals, while some others make a version close to a different branch because they believe otherwise.. they believe the branch near THEIR version is closest to the originals. I mean, Im just surprised to see modern Bibles being sortable into which branch they are from. Do you happen to know if that’s based on the beliefs of the ones making the version, like I said, or if they have other reasons such as wanting one close to the branch per se to use with fathers who had such? Anyway only if interested in replying further, and thanks again. And I hope you have a great day.

Brother, to me it's very simple. Any bible that will show you the textual variants in a footnote that have been utilized by Christians in those major branches is the historical Word of God. Take for example the ESV and the NKJV. Both will tell you for the most part what are the major textual variants either in the text or on the footnote. Sometimes we make a big deal out of textual variants and forget that Christians have always defended the same Word of God in the East, in the West and in Egypt. The message is the same everywhere. I personally think that there was an issue with the copyists in Egypt that skipped some portions of the Word of the God, especially in their copies of the gospels. But even so, giants of the orthodoxy like Athanasius and Cyril of Alexandria defended respectively the deity of Christ and the hypostatic union in the person of Christ with the texts handed down to them. Also, if you read the letters of the apostles (excluding the book of revelation), you will notice that the degree of convergence to one text is even greater for those major branches. Take for example the letter to the Galatians. Read it in the ESV, the NKJV, the EOB or the DRB and you will see for yourself that you have essentially the same letter of the apostle Paul to the Galatians in all those versions. And above all. Don't let the spirit of sectarianism lead you astray. Those Christians who will disagree with you on a particular textual variant are doing so based on historical fact. They are not agents of the devil. They are Christians doing their best to ascertain what the apostles wrote. Even if you disagree with their conclusions, especially on this matter, never forget that it is a grievous sin to break the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace (Eph. 4:3) or go against Christ's prayer that prayed that we should be all one (John 17:21).

Thanks for a great reply.

I'm late to the game in terms of making a comment on this post. However, I'll give it a shot anyway.

In the Introduction of the EOB New Testament, it states "The translation of the New Testament included in the EOB is based on the official Greek text published by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1904 (Patriarchal Text or PT)." And later it states "...even though the Patriarchal text is primary for the main body of the EOB/NT, constant reference has been made to the so-called Critical Text (CT) published by the United Bible Society (UBS/NA27 4th edition)."

So in reading the EOB/NT, I get to Matthew 1:6, which reads, "Jesse became the father of King David. David became the father of Solomon by her who had been the wife of Uriah." If I understand correctly, the second half of that verse in the Patriarchal text, if translated into English similarly, would instead read, "David the king became the father..." or "King David became the father..." (emphasis mine).

My questions are these: Why is the phrase "the king" in the second half of Matthew 1:6 missing? Is this a mistake? Is it an instance of the translator deciding to follow the Critical Text here, as hinted at in the Introduction? And if it is a case of following the Critical Text, what makes this edition of the NT distinctive? If it followed the Patriarchal text throughout, I would understand the significance of it. But if it largely follows the Patriarchal text, but then follows the Critical Text here and there, what makes it significantly different from any of the other NT translations that take an eclectic approach when it comes to following a given Greek NT edition?

I like the EOB/NT translation generally, but I am simply confused at seeing it deviate from the Patriarchal text so early (i.e., at Matthew 1:6).

Jeff,

Your observation about Matthew 1:6 seems accurate. It might seem to be a translation inaccuracy at first, as both the received text and Byzantine text have the word for "king" twice here, while the EOB only includes it one time. But upon noticing that the (Alexandrian) critical text is omitting the same words, the omission (in the EOB) is almost certainly due to the influence of those texts, rather than as an inaccuracy of translation.

And to JSJ respectfully,

The Eastern Orthodox Bible (EOB: see

here) does not say "Again, amen" in Matthew 18:19, nor does it say "or" instead of "and" in Matthew 20:22.

Also, the EOB in James 4:12 does not include the phrase, "and judge," (also the Majority Text F35 by Pickering does include this reading, but other MT editions do not). In a similar situation, the EOB does not include the phrase, "up into salvation" in 1 Peter 2:2. Also the difference listed in this article about Jude v. 4 is simply a translation difference for the word "δεσπότης", but the EOB also translated this word as "Lord" in Acts 4:24.

In your article where you mention the inclusion of the variant: Matthew 13:14 “spoken of by Daniel the prophet,” I think should be Mark 13:14. Also, Matthew 6:13b is still placed in angle brackets in the EOB, as is the name "Cainan" in Luke 3:36.

Lastly, I have a few concerns based on my notes of the Eastern Orthodox Bible (EOB):

The translation of Latreia as "divine service" in the EOB (e.g. Philippians 3:3) instead of "worship" or "serve" – clashes with the basic meaning of the passages in Acts 7:42, Hebrews 13:10 and Romans 1:25 of the EOB, where it is implied that it is possible to offer "divine service" to non-divine entities.

The translation of the term Gospel is variously changed to "Good News" in the EOB. Despite making this substitution broadly, the substitution is not done consistently, e.g. Romans 2:16, 1 Corinthians 9:18, Galatians 2:14 still use "Gospel." If you can keep the word Gospel in these places, why not in Romans 10:16, 2 Corinthians 9:13, 2 Corinthians 11:4, Galatians 1:6 (where they choose to insert scare quotes), 2 Thessalonians 1:8, 1 Peter 4:17, or in Revelation 14:6 (where the definite is represented by the translators as an indefinite); and furthermore why insert the word into Romans 1:3,17 ? Compare these verses for yourself and see what I mean. The EOB also inserted the word "only" in 1 Peter 3:3, similar to how the NASB and NKJV handle this verse with the interpolation of the word "merely." A similar change from definite to indefinite also exists in the EOB footnote for John 20:22, by the way.

In Philippians 2:6, the EOB translators followed the ASV and some more recent translations in the highly objectionable reversal of the meaning of the phrase "thought it not robbery to be equal with God" into the phrase "did not consider equality with God as something to be taken," or, "grasped."

I have personally seen and heard cults (whose name I will not mention here) rely on this highly, highly objectionable translation of Philippians 2:6 among other things to argue against the divinity of Christ.

In the EOB, brackets are placed in the text, in places like "through Jesus Christ" in Ephesians 3:9, or in the second part of John 16:16. These instances seem to be due to Alexandrian (or, as the EOB footnotes say, CT) influence.

In other passages, where the received text and Byzantine text agree, they are still omitted in the EOB. For instance, the word "Lord" in Mark 9:24 is omitted in the EOB (with no footnote, though that would not improve matters). The same happens with the phrase "of all the commandments" in Mark 12:29. Also the phrase "in the name of the Lord Jesus" in Acts 9:29. And the word "Amen" in John 21:25.

The EOB in Colossians 2:2 also changes the copulative conjunction in the phrase "and of the Father" to an explicative conjunction, then using that as a basis to compress the verse down to "God the Father," thereby reducing the subject of Paul's statement to two persons instead of three. However the EOB – it should be noted – does not follow the CT in this place, which it omits the three words "καὶ πατρὸς καὶ" entirely.

The EOB also does the same as the above again, in Third John verse 5, changing the conjunction in this verse, "to the brethren, and to strangers" to instead refer to these groups as being one and the same; namely, "brethren and strangers," which seems to be another critical text influence in the EOB.

Among some other changes, I am not sure why the EOB translators would choose to render "only begotten" as "unique" in John 1:18 – not to mention offering a different interpretation of Hebrews 11:17 (take a look at the EOB for yourself) – if they were ready to use the former term in John 3:16 and John 1:14. (1/2)

A few other changes:

– Mark 3:29 the EOB reads "sin" instead of "damnation" with no footnote, following the CT

– Mark 6:11 the CT removes the second part of the verse, but the EOB footnote marker erroneously marks the first sentence of the verse as being missing, instead of the second

– Mark 7:8 another doctrinally unusual footnote appears here

– Mark 13:33 the EOB omits "and pray" (no footnote)

– Mark 16:9-20 is bracketed from the main text

– Luke 6:1 "the second sabbath" is changed to "a certain sabbath" (no footnote of explanation)

– John 5:39 imperative changed to indicative

– John 8:59 and John 16:16, brackets added

– Acts 1:3 "infallible proofs" changed to "proofs"

– Acts 17:26 EOB omits the word "blood"

– Acts 18:7 EOB adds the word "Titus"

– 1 Corinthians 10:9 "Christ" changed to "Lord" (as in certain CT translations but not others)

– Ephesians 6:9 "your master" changed to "their master and yours" (follows the CT, no footnote; possibly implies that no saved master has an unsaved slave)

– 2 Thess. 1:8 EOB omits the word "Christ"

– 1 Timothy 6:5 EOB omits "from such withdraw thyself" (in the footnote)

– Titus 2:7 "incorruptibility" is not linked to "doctrine" in EOB (in διδασκαλίᾳ ἀδιἀφθορίαν, διδασκαλίᾳ is dative instead of accusative, unlike the other items, which are accusative and therefore modify it; also the word ordering is changed in the translation from the original ordering to remove "incorruptibility" as far away from "doctrine" as possible, while still keeping it inside the same verse.)

– Hebrews 3:1 EOB omits the word "Christ"

– Hebrews 3:16 has a different grammar to mean that all provoked instead of that some provoked, similar to the NKJV in this verse

– Jude verse 23, "others save with fear, pulling them out of the fire" changed to "You can save some of them, snatching them out of the fire with fear" (I've seen other translations of the Byzantine text that are similar to the KJV here)

– Revelation 6:3 "and see" removed (but not in vv. 1, 5 or 7)

Except where noted there are no footnotes for any of these deviations from Byzantine + TR, noting that they are such.

The footnotes that do exist, which I found reason to object to are in Luke 3:36, where the translators note that their own main text has a transcription error in it, also at Hebrews 1:8, and at Mark 7:8 and John 20:22 as previously noted.

I would also separately object to the EOB (and other popular) translation(s) of Titus 3:10, where "one who creates factions" is changed to "one who causes divisions." These are not exactly the same meanings. Comp. Luke 12:52, Second Cor. 6:14, and Genesis 1:4. Also Revelation 3:16, et cetera. "I know thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot: I would thou were cold or hot." Same thing for Jude 1:19 in the EOB -- "Those who separate themselves" is not exactly the same as those who are "divisive" or cause divisions, there is a subtle but important difference there.

-Andrew Tollefson

I considered that the Matthew 1:6 difference might be a nod to the Critical Text. However...I believe the general procedure in EOB in those cases is to call out the issue with a footnote if the CT is followed. Maybe the editors did not consider that to be a significant variant. It's just a shock to begin reading the EOB and see it begin to follow the CT right off the bat!

Andrew T,

It seems that your EOB-NT is somewhat different from the one I have from New Rome Press.

JSJ

James,

My hope is that they have addressed these concerns in the edition you have. I have just been looking at the publically available version linked Here for peoples' reference.

Post a Comment