We are about to meet

some manuscripts. Some of these, you

might encounter very often in the apparatus of the Greek New Testament. Others are relatively small, but they are

among the earliest witnesses to the readings they support.

In the course of

this lecture, I will mention links to supplemental materials as we go. I hope

that you will pause this video when a link appears, explore each resource, and

then return to the lecture. These

resources include images of manuscripts that can be viewed in fine detail.

Today I am going

to refer to the Alexandrian Text, the Western Text, and the Byzantine

Text. Hopefully in a future lecture I

will go into more detail about these terms.

For now, you can generally picture them as three forms of the text: the Alexandrian Text was used in Egypt, and

influenced the Sahidic version there.

The Western Text was used mainly but not exclusively in the Western part

of the Roman Empire, and influenced the Old

Latin text. The Byzantine Text was used in the vicinity of Constantinople,

and is generally supported by the majority of Greek manuscripts.

● We

begin with Papyrus 52. This is perhaps the oldest manuscript that

contains text from the New Testament. It

is small, about the size of a playing card.

It contains text from John 18:31-33 on one side, and on the other side

it contains text from John 18:37-38. Which

is not a lot of text. It was brought to

light by Colin H. Roberts in 1935.

The importance of Papyrus 52, which

is at the John Rylands Library in Manchester,

England, is its

age: it is probably from about the first

half of the 100s. There is a nice description of

Papyrus 52 (and other papyri fragments) by Robert Waltz at the Encyclopedia of New Testament Textual Criticism. In addition, Dirk Jongkind has a brief video about P52 on YouTube.

● Papyrus 104 is

another early papyrus fragment that is a top contender for the title “earliest

New Testament manuscript.” It was

excavated at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt by Grenfell and Hunt, and was

brought to light in 1997 by J. D. Thomas.

If Papyrus 52 is the earliest manuscript of John, Papyrus 104 is the

earliest manuscript of Matthew. The

handwriting used for P104 was executed in a fancier style than what is seen in

most other manuscripts; similar handwriting appears in some non-Biblical

manuscripts excavated at Oxyrhynchus, including one in which a specific date,

from the year 204 or 211, has survived.

Papyrus 104 contains

text from Matthew

21:34-37 on one side. The text on the other

side is very extremely badly damaged.

But the surviving damaged text there probably contains text from Matthew

21:43 and 45. This would mean that

Papyrus 104 is both the earliest manuscript of Matthew 21 and also the earliest

witness for the non-inclusion of Matthew 21:44.

Greg Lanier’s detailed analysis of

Papyrus 104 can be found online in Volume 21 of the TC-Journal, for 2016.

● Papyrus 23 is a fragment of the Epistle

of James, probably made in the early 200s.

It contains text from part of James chapter 1.

You can get a very good look at Papyrus

23 by visiting the website of its present home, the Spurlock

Museum in Urbana, Illinois.

● Papyrus 137 received some fame, before

its official publication, by being heralded as if it was from the first century;

it was called “First Century Mark.” It

turned out to be not from the first century.

However, this manuscript – a very small fragment containing text from

Mark 1:7-9 and Mark 1:16-18 – is the oldest copy of the text it preserves. Like several other early fragments, it has

made no impact on the compilation of the text of the New Testament.

● Papyrus 45 is much more substantial –

but it is still very fragmentary. When

it was made in the first half of the 200s, Papyrus 45 contained the four

Gospels and Acts. The order of books,

when the manuscript was made, is unknown.

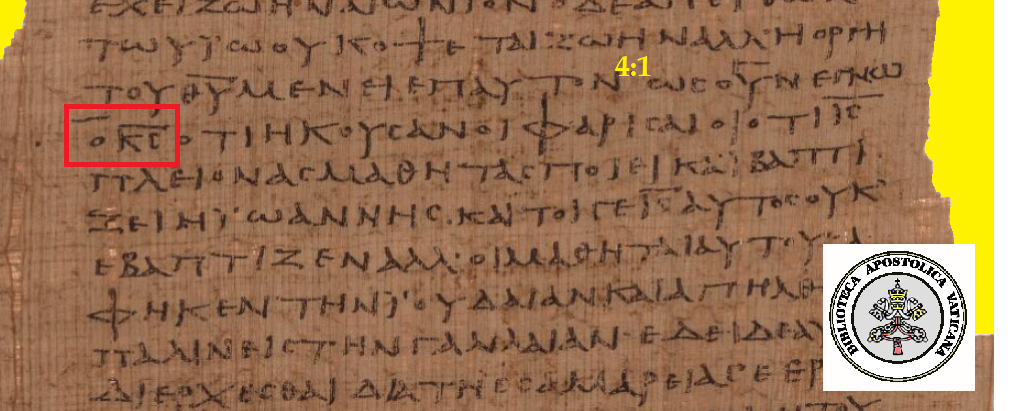

Its surviving pages at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin contain text

from Matthew 20 and 21, Mark 4-9, Mark

11-12, Luke 6-7, Luke 9-14, John 4-5, John 10-11, and Acts 4-17. A leaf in Vienna contains text from Matthew 25-26. This is the earliest known manuscript that

contains text from all four Gospels.

Papyrus 45 has several readings that

are especially interesting due to the impact they have on Hort’s Theory of the

Lucianic Recension. Hopefully we will take

a closer look at this in a future lecture, but for now, we can just sum it up

as the theory that the Byzantine Text – the text in the vast majority of Greek

manuscripts – originated as the result of an editorial effort by someone in the

late 200s – possibly Lucian of Antioch – who was combining readings from two earlier

forms of the text: the Alexandrian Text,

and the Western Text. Based on this

theory, Hort rejected readings in the Byzantine Text that were neither

Alexandrian nor Western, reckoning that they did not exist before the Byzantine

Text was made.

But in Papyrus 45, which is assigned

to the early 200s, there are some readings that are not supported by the

flagship manuscripts of the Alexandrian Text or the Western Text. Readings

in Mark 7:35, Acts 15:40, and many other passages show that it is hazardous to

assume that non-Alexandrian, non-Western readings should be rejected.

The text of Papyrus 45 does not agree

particularly strongly with Codex Vaticanus, and it does not agree particularly

strongly with Codex Bezae either. In the

parts of Mark where Papyrus 45 is extant, its closest textual relative is Codex

W – but Codex W’s text in those parts of Mark is not particularly Alexandrian

or Western either.

When Papyrus 45 was first studied, after

it was brought to light in the 1930s, there was a tendency to call its text

Caesarean, like the text of family-1.

But the late Larry Hurtado showed that whatever Papyrus 45’s text is, it

is not closely related to the Caesarean Text.

And while it repeatedly agrees with the Byzantine Text, it is not

consistently Byzantine either.

● Papyrus 46 is the earliest substantial

copy of most of the Epistles of Paul, basically arranged in order according to

their length, with Hebrews between Romans and First Corinthians. There is some uncertainty about how many

epistles the copyist intended to include in the codex. Part of this manuscript is at the Chester

Beatty Library in Dublin, and part of it is at

the University of

Michigan. Its most likely production-date is around

200, give or take 50 years. The text of

Papyrus 46 tends to agree with Codex Vaticanus, but not as strictly as one

might expect. For example, in Ephesians 5:9, Papyrus 46 agrees with the

Byzantine Text, reading “the fruit of the Spirit” instead of “the fruit of the

light.”

● Papyrus 66 contains most of the Gospel

of John, with some gaps due to incidental damage. It was found in Egypt in the early 1950s, and was

published in 1956. Its production-date

was initially assigned to around 200, but a wider range is possible. The copyist who wrote the text in Papyrus 66

made over 400 corrections of what he had initially written.

● Papyrus 75 is also assigned to around

200. It is a damaged but substantial

codex that contains text from Luke and John.

Its surviving text of Luke begins in chapter 3; its surviving text of

John ends in chapter 15. The text of

Papyrus 75 is close to the text found in Codex Vaticanus, but the two

manuscripts are not related in a grandfather-and-grandson kind of relationship. Page-views of Papyrus 75 can be found online

at the website of the Vatican Library.

Each of

the next three manuscripts was designed as a pandect, that is, a large

one-volume collection of the entire Bible.

We tend to assume that it is not unusual to have a single volume that

contains all of the books of both the Old Testament and the New Testament. But that is because we are part of a

post-printing-press generation. In the

world of manuscripts, Greek pandects of the Bible are rare.

● Codex

Vaticanus is a very important manuscript of the Bible, housed, along with many

other manuscripts, at the Vatican Library in Rome.

Its New Testament portion was not the subject of scholarly study until

the early 1800s, and since then its reputation has grown. Today it is generally regarded as the most

important manuscript of the New Testament.

Textually, Codex Vaticanus is the

paramount representative of the Alexandrian Text.

Vaticanus was produced in the early

300s. Its text, in the New Testament, is

formatted in three columns per page.

This is usually its format in the Old Testament books too, although in

the books of poetry the format is two columns per page. Codex Vaticanus does not contain the entire

New Testament; it has no text from First Timothy, Second Timothy, Titus,

Philemon, or the book of Revelation; a

text of Revelation is in the codex, written in minuscule lettering, but it is

not really the same codex.

Vaticanus

also does not contain the text of the book of Hebrews after Hebrews 9:14.

The lettering in Codex Vaticanus has

been extensively reinforced; that is, someone, long after the codex was made,

traced over the lettering, except where, rightly or wrongly, he thought that the

text was inaccurate. The exact date when

this was done is a matter of debate. I

suspect that Codex Vaticanus, before it ended up at the Vatican Library, was

previously in the hands of an important character in the 1400s named Bessarion,

and scribes working for Bessarion may have been responsible for sprucing it up

a bit. This did not materially affect

its text.

The entire manuscript can be viewed

page by page at the website of the Vatican Library.

● Codex

Sinaiticus is the wingman of Codex Vaticanus.

Its text is not as good, but it is more complete. The New Testament text of Codex Sinaiticus

has survived in more or less the same form in which it left its scriptorium in

the mid-300s. “More or less,” that is,

because a few centuries after its production, someone attempted to adjust many

of its readings, but those attempts can be detected. In addition to containing the text of every

book of the New Testament, Codex Sinaiticus also contains the Epistle of Barnabas and part of the Shepherd of Hermas.

Most of the text of Codex Sinaiticus

is Alexandrian. However, in the first

eight chapters of John, more or less, its text tends to be more like the

Western Text. It is as if the copyists

were working from an exemplar of the Gospels that was Alexandrian, but in these

opening chapters of John, their main exemplar was damaged, and so they used a

drastically different exemplar as their back-up.

That would be consistent with a

historical scenario that is mentioned by Jerome, who states that Acacius and

Euzoius, at Caesarea in the mid-300s, labored

to replace texts written on decaying papyrus in the library there with more

durable parchment copies. Whereas Codex

Vaticanus does not have the Eusebian Section-numbers in its margins in the

Gospels, Codex Sinaiticus does – but in a somewhat mangled form.

This indicates that Eusebius of

Caesarea was not involved in the production of Codex Sinaiticus, because it is

extremely unlikely that he would have allowed his own cross-reference system to

be presented so carelessly. At the same

time, as the place where Eusebius was bishop until his death, Caesarea

was one of the first places where the Eusebian Canons were used.

In addition, there are several clues

embedded in the text of Codex Sinaiticus that suggest that it was made at Caesarea, during the time when Acacius, an Arian, was

bishop there. I think it is very

probable that this is when and where it was made.

Details about the origin of Codex

Sinaiticus, and the quality of its text, have tended to be overshadowed by

stories about its discovery in the 1800s by Constantine Tischendorf at Saint Catherine’s

Monastery on Mount Sinai. In this lecture I will not go into detail

about all that, except to say, first, that the most generous interpretation of

Tischendorf’s account of his first encounter with pages from Codex Sinaiticus

is that he did not understand what he was being shown and what he was being

told, and, second, all of the pages that Tischendorf took should be returned to

the monastery from which they came.

Codex Sinaiticus has a secondary set

of section-numbers in its margin in Acts that is, for the most part, shared by

Codex Vaticanus. This indicates that

when these numbers were added, probably in the 600s, these two manuscripts were

at the same place.

Codex Sinaiticus has its own

website, CodexSinaiticus.org , and there one can find not only good photographs

of the manuscript but also some interesting information about its background

and how it was made.

● Next is

Codex Alexandrinus. This codex, from the early 400s, has

undergone significant damage: it is

missing the first 24 chapters of Matthew.

The surviving Gospels-text of Alexandrinus is particularly important

because it tends to support the Byzantine Text, unlike Vaticanus and

Sinaiticus. In Acts and the Epistles,

its text agrees much more often with the two flagship Alexandrian codices, but

this is a tendency, definitely not a two-peas-in-a-pod level of agreement. For Revelation, Codex A is the best

manuscript we have. The entire New Testament portion of Codex Alexandrinus can

be viewed page by page at the British Library’s website.

● The

worst Greek manuscript we have is Codex

Bezae, a diglot manuscript, with alternating pages in Latin, which was

produced in the 400s. It has undergone

some damage, but it still contains most of the four Gospels, in the order

Matthew – John – Luke – Mark, part of Third John in Latin, and most of the book

of Acts.

More important than its

production-date is the date of the readings that it supports: many of them are supported by Old Latin

witnesses, and by early patristic writers who used what is called the Western

Text.

The high level of textual corruption

in Codex Bezae makes the text found in relatively young manuscripts look

excellent in comparison. Codex D’s text

demonstrates that what really matters is not the age of a manuscript, as much

as how well the copyists in the transmission-line of a manuscript did their

job.

Once one comes to terms with the

awful quality of Codex Bezae’s text, though, many of its readings are awfully

interesting. It echoes a time in the

text’s history when copyists prioritized conveying the meaning of the text – or

what they thought was its meaning – above the form of the text found in their

exemplars.

Codex Bezae can be viewed online

page by page at the University

of Cambridge’s Digital

Library.

● Also

from the 400s, and probably earlier than Codex Bezae, is Codex Washingtonianus. Codex

W was acquired by the American businessman Charles Freer in 1906. It is the most important Greek

Gospels-manuscript in the United

States.

Part of what makes Codex W important is not only its age, but its

attestation to different forms of the text collected in a single volume: its text in Matthew is strongly

Byzantine. Its text in Mark 1:1 to Mark

1-5 is similar to Western Text. Its text

in the rest of Mark tends to agree

with the surviving text of Papyrus 45, at least in the parts where P45 is

extant. In Luke, up to chapter 8, its

text is Alexandrian, but the rest of Luke tends to agree with the Byzantine

Text. In the first four chapters of

John, Codex W has supplemental pages, copied from a different exemplar than the

rest. In the rest of John, it tends to

agree with the Alexandrian Text.

This has led some researchers to

suspect that although most of Codex W appears to have been made in the 400s, it

may be a copy of an earlier codex that was based on exemplars that had been

partly destroyed in the Diocletian persecution, in the very early 300s, just

before Codex Vaticanus was made.

Page-views of Codex W can be accessed at the website of the Center for the

Study of New Testament Manuscripts.

● Codex Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus, also

known as Codex C, is a palimpsest. Its

surviving pages contain text from almost every book of the New Testament, as

well as pages from some of the books of Poetry in the Old Testament, and two

apocryphal books. It was made some time

in the 400s. Its text is somewhat

Alexandrian, with significant Byzantine mixture. It is one of the few Greek manuscripts that

support the reading “six hundred and sixteen” as the number of the beast in

Revelation 13:18.

The parchment of Codex C was

recycled to provide material on which some of the works of Ephraem the Syrian

were written; this accounts for the name of the manuscript. Its Biblical text was established in the

1840s, after much effort, by Constantine Tischendorf, the same individual who

brought Codex Sinaiticus to the attention of European scholars. The text has undergone extensive correction.

● 0176 is a fragment, probably produced in the 400s, that contains

text from Galatians 3:16-24. This manuscript was excavated from Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, which is somewhat

intriguing, because the text of this fragment is thoroughly Byzantine, not

Alexandrian.

● The Purple Triplets is my pet name for

three uncial manuscripts from the mid-500s:

Codex N, Codex O, and Codex Σ. Codex N is also known as 022, Codex

Petropolitanus Purpureus. Codex O is also known as 023, Codex

Sinopensis. It contains text from the

Gospel of Matthew. And Codex Σ is also known as 042,

Codex Purpureus Rossanensis, or the Rossano Gospels. It contains text from Matthew and Mark.

These are not the only Greek uncial

manuscripts written on purple parchment.

What is especially interesting about these three is that they are

related to each other like siblings, copies of the same master-copy. Codex Σ is known not only for its mainly Byzantine

text, but also for its illustrations, which can be viewed at http://www.codexrossanensis.it .

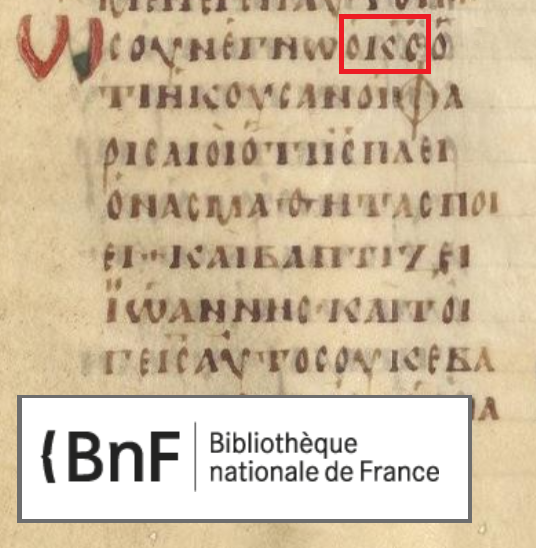

● Codex Regius, also known as Codex L, contains

most of the text of the four Gospels. It

was probably made in the 700s, probably by an Egyptian copyist. Codex L is one of six Greek manuscripts that

attest to both the Shorter Ending and the Longer Ending of Mark. Codex L also has a large distinct blank space

in the Gospel of John where most manuscripts have John 7:53-8:11, the story of

the adulteress.

● Codex Pi, also known as Codex

Petropolitanus, is a Gospels-manuscript assigned to the 800s. Its text is a very early form of the

Byzantine Text.

● Codex K, also known as Codex Cyprius,

is another Gospels-manuscript that was also probably produced in the 800s. In the first 20 verses of the Sermon on the

Mount in Matthew 5, compared to the text in Codex Sinaiticus, the text of Codex

Cyprius is much closer to the original text.

● Minuscule 2474, the Elfleda Bond

Goodspeed Gospels, from the 900s, contains an example of the text of the

Gospels that dominated Greek manuscript-production in the Byzantine

Empire. This manuscript can

be viewed page by page at the website of the Goodspeed Manuscript Library of

the University of

Chicago.

There are also several clusters, or

groups, of manuscripts, that share readings that indicate that they share the

same general line of descent:

In the Gospels, the text of some

members of a group of manuscripts that display a note called the Jerusalem Colophon is above average

importance.

Readings shared by the main members

of Family 1 in the Gospels, best

represented by minuscule manuscripts 1, 1582, and 2193, probably echo an

ancestor-manuscript from the 400s.

Members of Family 13 in the Gospels tend to echo an ancestor-manuscript with

many reading that diverge from the Byzantine standard.

Also, in the General Epistles,

members of the Harklean Group echo a

form of the text that has some unusual readings that are earlier than Codex

Sinaiticus.

Some other minuscules, such as

minuscules 6, 157, 700, 892, and 1739, are as important as some of the

uncials. Their existence should remind us

that when we ask how much weight ought to be given to a particular manuscript,

the primary consideration should not be “How old is it”, but “How well did the

copyists in its transmission-stream do their job?”.

No manuscript sprang into being out

of nothing, and any manuscript, early or late, if it is independent from

another known manuscript, has the potential to contribute something to a

reconstruction of the text of the New Testament.

To get some idea of the appearance

of New Testament manuscripts, I encourage you to explore the online

presentations of manuscripts at the following institutions:

Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai, the Vatican

Library, the British Library, the National Library of France, the Walters Art Museum, the Goodspeed Manuscript Collection

at the University of Chicago, the

Kenneth W. Clark Collection at Duke

University, and the Center for the Study of New

Testament Manuscripts.