The 20th video lecture in the series

Introduction to NT Textual Criticism is accessible at

YouTube and at

Bitchute. This lecture is 32 minutes long. Here's an extract:

Justin Martyr, who was martyred in

the 160s, used this text in his composition Dialogue

With Trypho, chapter 103. Commenting

on Psalm 22, verse 14, he wrote, “In the

memoirs which, I say, were drawn up by His apostles and those who followed

them, it is recorded that His sweat fell

down like drops of blood while He was praying.”

Reckoning that the Gospel of Luke was not

written before the early 60s, this implies that Justin’s copy of the Gospel of

Luke was separated from the autograph of the Gospel of Luke by less than a

century.

About

two decades after Justin, Irenaeus wrote the Third Book of his composition Against Heresies. In the 22nd chapter, Irenaeus used

Luke 22:44, mentioning that if Jesus had taken nothing of Mary, that is, if He

had not experienced a physical human nature, he would not have eaten food harvested from the earth, He would

not have become hungry, or weary, “Nor would He have sweated great drops of blood.”

Irenaeus’ contemporary Tatian

included Luke 22:43-44 in his Diatessaron,

around the year 172. Around the year

360, as Ephrem Syrus composed his commentary on the Diatessaron, he also mentioned the detail about Jesus’ sweat

becoming like drops of blood.

Also, in Ephrem’s Carmina Nisibena, in Hymn 35, part 18, Ephrem

pictures the devil saying about

Jesus, “While He was praying I saw Him and was glad, because He changed color

and was afraid: His sweat was as drops of blood, because He felt that His day had

come.”

In the early 200s, the writer

Hippolytus referred to Luke 22:44, near the beginning of chapter 18 of Against Noetus. In the course of giving examples of the

contrast between Jesus’ divinity and humanity, Hippolytus wrote that “In agony He sweats blood, and is

strengthened by an angel.”

The first patristic writer to mention

manuscripts that do not support Luke 22:43-44 is Hilary of Poitiers. Around 350, in Book 10 of his Latin composition

De Trinitate, in part 41, Hilary wrote, “We cannot overlook that in very many Greek and Latin codices

nothing is recorded about the angel’s coming, and the sweat like blood.”

Despite acknowledging such

manuscripts, Hilary does not offer a judgment on whether the passage has been

omitted in the copies where it is absent, or interpolated in the copies in

which it is found. He seems to have been

less concerned about reaching a correct verdict on the textual question and

more concerned about promoting correct theology.

He said that heretics should not be

encourage by the idea that Jesus’ weakness is confirmed by the need for an

angel to strengthen Him, and that His sweat should not be construed as a sign

of weakness. And like Irenaeus, he

points out that the bloody sweat demonstrated the reality of Jesus’ physical

body. When he states, “We are forced to the conclusion that all

this happened on our account.” He seems content to use the text.

In 374, Epiphanius of Salamis made

some very interesting statements about Luke 22:43-44. In Panarion

19:4, he quoted these verses an example of passages that Arians use to show

that Jesus sometimes needed assistance from others, or that He was inferior to

the Father: “And it says in the Gospel according to Luke, ‘There appeared an angel

of the Lord strengthening Him when He was in agony, and He sweat; and His sweat

was as it were drops of blood, when He went out to pray before His

betrayal.”

It should be noticed that Epiphanius

quoted verse 43 with the reading “angel of the Lord.”

In

Panarion 61, Epiphanius used the

passage again in the same way. He used

the passage for doctrinal purposes, and stated that without the display of

agony and sweat pouring from His body, the Manichaeans and Marcionites might

seem reasonable in their theory that Christ was an apparition, and not

completely real.” He emphasizes how

Jesus’ sweat like blood showed that “His flesh was real, and not an apparition.”

Epiphanius

claims in Panarion that Arius cited this very passage from the Gospel of

Luke in an attempt to demonstrate the subordination of the Son to the Father.

So far, we could read Epiphanius’

remarks and think that the only form of the text he knew included verses 43 and

44. But in Ancoratus, chapter 31, Epiphanius wrote that the passage “is found

in the Gospel according to Luke in

unrevised copies.” Then he said, “The orthodox have removed the passage,

frightened and not thinking about its significance.” Coming from someone who seemed ready to blame heretics for

bad weather, this is a remarkable statement.

Epiphanius

uses Luke 22:43-44 again in Ancoratus chapter

37 as evidence that Jesus was truly human, and that His sweat shows that He was

physical.

Around the year 405 in Asia Minor, Macarius Magnes, in the third part of the work

Apocriticus, quoted from a pagan

writer, probably Hierocles, a student of Porphyry. Hierocles lived in the late 200s and early

300s.

When this pagan writer

objected to Jesus’ statement, “Do not fear those who kill the body,” he wrote

that Jesus Himself, “being in agony,” prayed that His sufferings should pass

from Him.” The

term “being in agony” here is probably

a recollection of Luke 22:43, because this term is used there, but not in the

parallel-passages.

For the testimony

of Amphilochius of Iconium, who lived from about 340 to about 400, we rely on a

collection of extracts in the medieval manuscript Athous Vatopedi 507, from the

1100s. A note simply says: “Of Amphilochius bishop of Iconium, on the

Gospel of Luke: it states there, “Being

in agony, He prayed more earnestly.”

There is some reason to wonder

whether Didymus the Blind, or someone else, was the author of the Greek

composition called De Trinitate that

is attributed him. Some interpretations of

the author are different from interpretations expressed by Didymus in some

other works. But, theologians do

sometimes change their views. Whoever

wrote De Trinitate, he made an

accurate quotation of Luke 22:43 in Book

3, Part 21.

Ambrose of Milan, in the late 300s,

in his commentary on Luke, seems to use a text that did not include verses 43-44; he does not mention the appearance of an

angel and he does not mention that Jesus’ sweat became like drops of blood.

John Chrysostom is yet another

patristic writer who used Luke 22:43-44.

Once he did so in a comment on Psalm 109. And once he did so in the course of his 83rd Homily on the Gospel of

Matthew, which covers the parallel-material in Matthew 26:36-38.

In

Homily 83 on Matthew, Chrysostom does

not say that he has put down the text of Matthew and has turned to the text of Luke. But after referring to Jesus’ prediction of

Peter’s denials, and Peter’s insistence that he will never deny Jesus,

Chrysostom transitions to the contents of Luke 22:43, stating, “And He prays

with earnestness, in order that the thing might not seem to be acting. And sweat flows over Him for the same cause

again, even that the heretics might not say this, that His agony was a

pretense. Therefore there is a sweat

like blood, and an angel appeared strengthening Him, and a thousand sure signs

of fear.”

After interpreting this for

several sentences, Chrysostom returns to the text of Matthew 26:40.

We

will reconsider the significance of this after we have seen the testimony of

the cluster of manuscripts known as family 13.

For now, let’s go on to the next

patristic reference.

The testimony of John Cassian should

not be overlooked, even though his name does not appear in the textual

apparatus for Luke 22:43-44 in the UBS Greek

New Testament or the Nestle-Aland compilation. John Cassian traveled widely: to the Holy Land, to Egypt, and to Rome,

before residing in what is now France

in about 415. In his First Conference of Abbot Isaac on Prayer,

also known as the Ninth Conference,

in chapter 25, Cassian states that the Lord, “in an agony of prayer, even shed forth drops of blood.”

Jerome,

in Against the Pelagians, Book 2,

part 16, shows that he was aware of some copies that had Luke 22:43-44, and

some copies that did not. In 383, he

included this passage in the Vulgate. Later,

in Against the Pelagians, he wrote

that these words – the words we know as Luke 22:43-44 – are “In some copies, Greek as well as Latin, written

by Luke,” which implies that Jerome also knew of copies in which the verses

were not included.

Theodore of Mopsuestia, a

contemporary of Jerome who worked mainly in Syria

and Cilicia, also had Luke 22:43-44 in his

Gospels-text. In 1882, the researcher H.

B. Swete published a collection of some fragments from Theodore’s works, and

one of them includes a full quotation of Luke 22:43-44.

Only slightly later comes Theodoret

of Cyrrhus, who famously oversaw the withdraw of 200 copies of the Diatessaron in his churches. In 453, Theodoret wrote Haereticarum Fabularum Compendium, and in this work, after

presenting Jesus’ statement in John 12:27, he says that Luke taught more

clearly how Jesus was indeed suffering, when He was in agony, and he proceeds

to use part of verse 44.

Now we come to the testimony of

Cyril of Alexandria, who died in the year 444.

In Cyril of Alexandria’s Sermon

146 and Sermon 147 on the Gospel

of Luke, Cyril describes the events in Gethsemane

in Luke 22, but he does not mention

the appearance of an angel, and he does not

mention Jesus being in agony or shedding drops of sweat like blood.

He states, “Everywhere we find Jesus

praying alone, you may also learn that we ought to talk with God over all with

a quiet mind, and a heart calm and free from all disturbance.” This is not the sort of thing one says when one

is reading a text that says that Jesus is praying in agony, and sweating huge

drops of blood.

Cyril says in Sermon 147, “Let

no man of understanding say that He offered these supplications as being in

need of strength or help from another – for He is Himself the Father’s almighty strength and

power.” Cyril does not come out and say

that he rejects the idea that an angel appeared and strengthened Jesus, but he

comes very close to doing so.

Severus of Antioch, in the first

half of the 500s, supplies some additional information about the text used by

Cyril. In an extract from the third

letter of the sixth book that he wrote to “the glorious Caesaria,” Severus stated

the following:

“Regarding the

passage about the sweat and the drops of blood, know that in the divine and

evangelical Scriptures that are at Alexandria,

it is not written. Wherefore also the

holy Cyril, in the twelfth book written by him on behalf of Christianity against

the impious demon-worshipper Julian, plainly stated the following:

“‘But, since he

said that the divine Luke inserted among his own words the statement that an

angel stood and strengthened Jesus, and his sweat dripped like blood-drops or

blood, let him learn from us that we have found nothing of this kind inserted

in Luke’s work, unless perhaps an interpolation has been made from outside

which is not genuine.

The books

therefore that are among us contain nothing whatever of this kind. And so I consider it madness for us to say

anything to him about these things. And

it is a superfluous thing to oppose him regarding things that are not stated at

all, and we shall be very justly condemned to be laughed at.’”

Then Severus says: “In the books therefore that are at Antioch and in other

countries, it is written, and some of the fathers mention it.” He names “Gregory the Theologian” and John

Chrysostom as two examples. Then he says

that he himself used this text, “in the sixty-fourth homily.”

In this way, Severus

drew his reader’s attention to Emperor Julian’s use of the passage in the

mid-300s, and to Cyril of Alexandria’s rejection of the passage in the early

400s, and to the acceptance of the passage in Antioch, and by Gregory of Nazianzus, by John

Chrysostom, and by Severus himself.

Severus’ testimony

is particularly significant because he specifies that the copies in Alexandria

lacked the passage.

Later, in the 600’s, a writer named

Athanasius, Abbot of Sinai, is credited with yet another text-critically

relevant statement about Luke 22:43-44.

Amy Donaldson, in her 2009 dissertation, Explicit References to New Testament Variant Readings Among Greek and

Latin Church Fathers, included his statement:

“Be aware that some attempted to delete the drops of blood, the sweat of Christ, from

the Gospel of Luke and were not able.

For those copies that lack the section are disproved by many and various

gospels that have it; for in all the gospels of the nations it remains, and in

most of the Greek.”

There is also a marginal note, preserved

in minuscule 34, that states that “the report about the sweat-drops is not in

some copies, but Dionysius the Areopagite, Gennadius of Constantinople,

Epiphanius of Cyprus, and other holy fathers testify to it being in the

text.”

We could examine more patristic

support for Luke 22:43-44, from Augustine and Nestorius, for example. But let’s go back to the evidence from Chrysostom.

Why, in Homily 83 on Matthew, does he take a detour to comment on Luke

22:43-44? It cannot be absolutely ruled

out that he just wanted to cover a parallel-passage. But another possibility is that by the time

John Chrysostom wrote Homily 83 on

Matthew, it was already customary that when the lector read the

Gospels-reading for the Thursday of Holy Week, after reading Matthew 26:39, he

also read Luke 22:43-44.

John’s brief detour into Luke 22

interlocks very snugly with this custom.

In addition, in Codex C, a secondary hand has written the text of Luke

22:43-44 in the margin near Matthew 26:39.

This brings us to the evidence from

the cluster of manuscripts known as family 13.

In most members of family-13, Luke 22:43-44 appears in Luke, either in

the text or margin after Luke 22:42. Most

of the members of family 13 also have these two verses embedded in the text of

Matthew after 26:39.

The evidence from minuscule

1689, a member of family 13, is very helpful.

This manuscript was lost for several years, but has been found safe and

sound in the city of Prague. It has Luke 22:43-44 in the text of Luke, and

alongside Matthew 26:39, there is a margin-note instructing the lector to jump

to Section 283 in the Gospel of Luke – that is, to jump to Luke 22:43-44.

Many other manuscripts have similar

notes in the margin at this point, as part of the lectionary apparatus.

It does not require a long

leap to deduce what has happened in family 13:

instead of resorting exclusively to margin-notes to instruct the lector

to jump from Matthew 26:39 to Luke 22:43-44 and then return to Matthew 26:40, someone

whose work influenced members of family 13 simplified things for the lector, by

combining the parts of the lection in order within the text of Matthew.

Some commentaries have misrepresented this as

if it implies that the passage is not genuine.

But the evidence in family 13 just shows that a passage that was regarded

as part of the text of Luke was embedded into the text of Matthew after 26:39

for liturgical purposes.

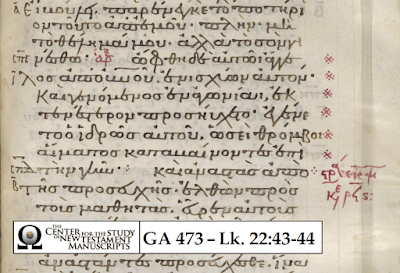

On a related point: when Luke 22:43-44 is accompanied by one or

more asterisks, such as in minuscule 1216, the default deduction should not be

that the purpose of the asterisks was to express scribal doubt, but to serve as

part of the lectionary apparatus, drawing attention to the two verses that were

to be read after Matthew 26:39 in the lection for Maundy Thursday.

So:

was Luke 22:43-44 initially present, or initially absent? The passage is supported by a broad array of

manuscripts, plus the manuscripts of over 20 patristic writers, and a couple of

non-Christian writers. Four patristic

writers – Hilary, Epiphanius, Jerome, and Athanasius of Sinai – show that they

were aware that verses 43-44 were not supported in all copies, but nevertheless

they favored the inclusion of the verses. Epiphanius

even said that orthodox individuals had attempted to remove the passage.

One Latin writer – Ambrose of Milan – did not have verses 43 and 44 in

his text of Luke 22.

And one Greek writer, Cyril of Alexandria, from the 400s, definitely did

not have verses 43-44 in his text.

The most ancient evidence, from

Justin, Tatian, and Irenaeus, includes the passage. The most

geographically diverse support points in the same direction. And support for these verses does not come

only from authors with only one doctrinal

view.

Plus, internally, nothing in the

surrounding material calls for the insertion of additional material. Bart Ehrman has proposed that verses 43-44 do

not look like something Luke would write, on the grounds that Luke had an

interest in portraying Jesus as “imperturbable.” However, Luke reports about several actions of

Jesus in which His disposition is far from stoical or disinterested, including

His criticism of the synagogue-ruler in chapter 13, and His weeping over the

city of Jerusalem

in chapter 19. There is no substantial

case based on internal evidence for the idea that verses 43-44 could not

originate with Luke.

When we look at the external

evidence that supports Luke 22:43-44, the question should not be “Did someone remove these verses from the

text of Luke,” but “Why did someone remove these verses

from the text of Luke?”

It is virtually unique to see a

Christian writer assert that “the orthodox” tampered with the Gospels-text, and

to imply that some orthodox believers revised the text in a way that was

influenced by their fear.

In the 100s, the second-century

writer Celsus, in a statement preserved by Origen, claimed that some believers

“alter the original text of the gospel three or

four or several times over, and they change its character to enable them to

deny difficulties in face of criticism.”

There’s no way to tell if Celsus saw what he says he saw, but it can’t

be ruled out that he did indeed notice Christians making changes to the

Gospels-text, and that because some of those changes appeared to him to relieve

perceived difficulties in the text, he naturally believed that this was the

motivation for the changes.

However,

he might have seen, and misunderstood, something else: textual adjustments that were not made to minimize

interpretive difficulties, but to render the text easier to use when it was

read in church-services.

One

of those adjustments may have involved a liturgical feature pointed out by John

Burgon in The Revision Revised.

Here I slightly paraphrase his

observations:

“In

every known Greek Gospels lectionary, verses 43-44 of Luke 22 follow Matthew

26:39 in the reading for Maundy Thursday.

In the same lectionaries, these

verses are omitted from the reading for the Tuesday after Sexagesima – the

Tuesday of the Cheese-eaters, as the those in the East call that day, when Luke

22:39-23:1 used to be read.

Furthermore,

in all ancient copies of the Gospels which have been accommodated to

ecclesiastical use, the reader of Luke 22 is invariably directed by a marginal

note to skip over these two verses, and to proceed from verse 42 to verse 45.

What

is more obvious, therefore, than that the removal of verses 43 and 44 from

their proper place is explained as a side-effect of a lection-cycle of the

early church?

Many manuscripts have been

discovered since the time of Burgon, but in general, what he describes is

accurate: Luke 22:43-44 is embedded

after Matthew 26:39 in the lection for Maundy Thursday, and it is left out of

the lection assigned to the Tuesday after Sexagesima Sunday.

The customary transfer of Luke

22:43-44 into the text of Matthew, when the text was read during Easter-week, may

explain the sudden detour that Chrysostom took into this passage in the course

of his Homily 83.

A scenario that explains the most

evidence in the fewest steps is that when an attempt was made to revise the

text for liturgical reading, one group of liturgical revisors took verses 43

and 44 out of Luke 22, but failed to re-insert them into Matthew 26. As soon as these verses dropped out of the

text, the shorter reading was defended along the same lines that we see Cyril

of Alexandria use to defend it.

We do not have hard evidence of this

particular liturgical step of revision being undertaken in the second century,

but the elegance of Burgon’s explanation is a strong factor in its favor. Plus, this theory accounts for the

correspondence between this particular feature in the Easter-time lections, and

the very similar contrast between forms of the text with and without the

passage.

So:

I conclude that Luke 22:43-44 was an original part of the Gospel of Luke.

I also conclude that its removal, in

the second century, was probably not

the result of some copyist’s desire to get rid of what he considered a

problematic passage; nor was it the result of a heretic’s

desire to remove a text that demonstrated the physicality of Jesus’ body. Instead, it occurred when orthodox believers transferred

verses 43 and 44 into Matthew, after 26:39, conforming to their Easter-time custom,

but failed to retain it in Luke, again reflecting their early Eastertime liturgy. As a result, these two verses fell out of the

text.

This influenced texts known to

Hilary, to Ambrose, and especially Cyril

of Alexandria. It affected the text that

was translated into Sahidic, and the Greek text that was translated into Armenian,

and the Armenian text that was translated into Georgian. But as Athanasius the Abbot of Sinai stated,

although some attempted to delete the drops of blood from the Gospel of Luke, the

legitimacy of the passage is shown by the “many and various Gospels-manuscripts

in which the passage is read.”

Luke 22:43-44 should therefore be

respected and cherished for what it is:

part of the Word of God.