At the

|

| Vincenzo Colosimo |

Apparently some of the mobsters in

Eventually, with the involvement of Harold R. Willoughby,

the

Lectionary 1599 was made in the 800s or 900s, and its text is written in two columns per page measuring approximately 29 x 22 cm. It has endured significant damage, but plenty of pages have survived which contain text from the Gospels. Its text, like most lectionaries, is essentially Byzantine. A few textual features may be mentioned:

Image 122: Luke 22:4 includes και γραμματευσιν, similar to the reading in C, N, P, 157, 700.

Image

190: Mark 15:28 is not in the text.

Image

228: In Matthew 27:55, εκει appears

after γυναικες.

Images

134, 135,

& 136: John 13:3-17 follows the end of Matthew 28,

and is followed by text from Matthew 26:21.

(This liturgical arrangement for Maundy Thursday explains why, in GA

225, John 13:3-17 is found after after Matthew 26:20.)

Images

235, 236,

& 237

– Mark 16:9-20 is the third of the eleven Heothina readings.

Image 242 – In John 21:1, the incipit-phrase (used to begin the reading, in the lower right-hand column 0f text) includes αὐτοῦ ἐγέρθεις ἐκ νεκρῶν, a reading also found in Γ (036) f13 1241 and 1424.

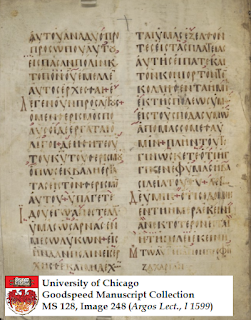

Image

248 – In Luke 10:8-10, near the end of the first column of text, the scribe

made a parableptic error when his line of sight drifted from εἰσέρχησθε καὶ in

10:8 to καὶ μὴ δέχωνται in 10:10. Also,

in Luke 10:11, the text of l1599

includes (“from your feet”).

Image 261 – In a list of feast-days in October, the saints honored on Oct. 7 are listed as Sergius and Bacchus. The saint honored on October 8 is listed as Saint Pelagia. This implies that John 8:3-11 was initially included in the lectionary, before it was damaged. This arrangement also explains why the story of the adulteress is found in family 13 in Luke 21, shortly after where the reading for Saints Sergius and Bacchus (Luke 21:12-19) is located. This kind of textual transplant was simply for the convenience of the lector.

8 comments:

Thanks for this, James. I am interested in your comments about texts that were displaced in continuous manuscripts to conform to the order in lectionaries. You write, "This kind of textual transplant was simply for the convenience of the lector". Are we to imagine that the text in question was inserted in the novel location in a single step by a copyist (to help lectors), or was the text added first to a margin (e.g. by a lector) and then subsequently incorporated into the main text by a copyist? If the displaced texts were added by a copyist (not via a margin) to help lectors, why were some texts added and not others? Should we assume that such displacements generally happened via margins? We can note that the duplication of John 13:3-17 in 225 was to the end of Matthew, where there may well have been plenty of space for a lector to add it to a manuscript. We can also note the displacement of Rom 16:20b to the end of the letter.

Van Lopik discussed the influence of the lectionary on the displacement of texts. Has anyone else published on this? Is there a list of such cases?

Richard Fellows,

<< Are we to imagine that the text in question was inserted in the novel location in a single step by a copyist (to help lectors), or was the text added first to a margin (e.g. by a lector) and then subsequently incorporated into the main text by a copyist? >>

In the case of the PA following Luke 21:38 in f13, the text was taken out of John so that the Pentecost lection (Jn. 7:37-52 + 8:12) would be one continuous uninterrupted segment of text, and put into Luke after 21:38 (as the reading for Oct. 8)

<< If the displaced texts were added by a copyist (not via a margin) to help lectors, why were some texts added and not others? >>

I might need more details to know to which text(s) you refer, but the general answer is that some lections were mixtures of different passages from different Gospels. Luke 22:43-44 is usually not transplanted into the text of Matthew - but it is in f13 - but there is a lectionary-related note about it in the margin of Matthew in quite a few MSS.

You mentioned both the PA and a Luke 22:43-44. Does the displacement of these texts have anything to do with the fact that they are both absent from many ancient manuscripts? Did someone find Luke 22:43-44 in a lectionary manuscript and, being unable to find it in his/her continuous manuscript, did he add it to the margin of his continuous manuscript? That is to say, did Luke 22:43-44 jump from a Lectionary manuscript to the margin of a gospels manuscript that lacked these verses? Are transpositions of large chunks of text evidence of earlier absence?

Richard,

<< Does the displacement of these texts have anything to do with the fact that they are both absent from many ancient manuscripts? >>

Yes, I would say so - though I wouldn't say "many."

<< Did someone find Luke 22:43-44 in a lectionary manuscript and, being unable to find it in his/her continuous manuscript, did he add it to the margin of his continuous manuscript? >>

No; I don't think that's quite how it happened. But this sort of question is better addressed when investigating specific passages, rather than a general description of one MS.

I'm still confused about what your understanding is. By what sequence of events did Luke 22:43-44 move to Matthew's gospel in F13? How is this related to the absence of the verses from several manuscripts?

Richard Fellows,

Well, leaving the Argos Lectionary to one side, I would point to my analysis of Luke 22:43-44, elsewhere here at the blog:

https://www.thetextofthegospels.com/2020/12/video-lecture-20-luke-2243-44-jesus-in.html .

Hello gentlemen...I wanted to let you know that this lectionary originally came from Argos Karia in Greece from my grandfather, Mike Biskos... He sold it in 1930 I believe 1932 and then whoever he sold it to sold it to University of Chicago.

I believe that he got it from his great great grandfather, if I recall something about the church burning from the Italian war when they invaded Argos.. My family it's extremely proud of our beloved grandfather, my mother's father... He trturnrd to Greece in the early 1980s to finished his life from where he was born...

Mike Biskos worked at Jimmy Colisimo's restaurant as a cook/manager and kept the restaurant up after Colisimo was murdered in front of the restaurant in 1920...My grandfather came over through Ellis Island in the 20 teens

Post a Comment