In Luke 2:22, there is a mildly famous – or infamous – textual variant which involves the Textus Receptus, the base-text of the KJV: did Luke write that “the days of her [that is, Mary’s] purification according to the law of Moses were accomplished”? That is how the passage is read in the KJV. The NKJV, MEV, the Rheims New Testament, the New Life Version, the NIrV, and the Living Bible read similarly. The phrase is different, however – referring to the days of their purification – in the ASV, CSB, EHV, EOB-NT, ESV, NASB, NET, NLT, NRSV, and WEB. (The NIV inaccurately avoids saying either “her” or “their,” and simply says vaguely that “the time came for the purification rites.” The Message hyper-paraphrase makes the same compromise, saying that “the days stipulated by Moses for purification were complete.” Other versions that have rendered the passage imprecisely include the CEV, ERV, and GNT.)

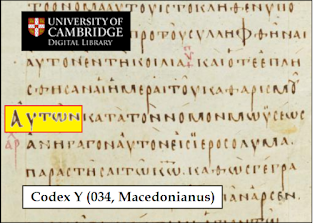

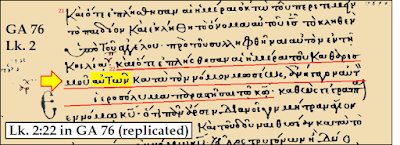

The difference in English reflects a difference in Greek: the KJV’s base-text (and the base-text of the Geneva Bible in the 1500s) says αὐτῆς, which means “her,” while the base-text of the EHV, EOB-NT, WEB, etc., reads αὐτῶν, which means “their.” The text compiled by Erasmus in 1516, and the text printed by Stephanus in 1550, and the Nestle-Aland/UBS compilations have αὐτῶν.

This little

difference is a big deal to some champions of the KJV, who regard the KJV’s

base-text as something which was “refined seven times” (cf. Psalm 12:6) in the

course of the first century of the printed Greek New Testament. D. A. Waite wrote as if the reading αὐτῶν implies that Jesus was a sinner:

“The word her is

changed to their, thus making the Lord Jesus Christ One Who needed

"purification," and therefore was a sinner!” (p. 200, Defending

the King James Bible, 3rd ed., Ó 2006 The Bible for Today Press) Will Kinney, a KJV-Onlyist,

has written, “The reading of HER is

admittedly a minority reading, but it is the correct one.”

In 1921, William H. F. Hatch, after investigated this variant, reported in the 1921 (Vol. 14) issue of Harvard Theological Review (pp. 377-381) that “The feminine pronoun αὐτῆς is found in no Greek manuscript of the New Testament.” Quite a few manuscripts have been discovered since 1921, but I have not found any Greek manuscripts that support αὐτῆς (though it is possible that αὐτῆς might be found in very late manuscripts made by copyists who used printed Greek New Testaments as their exemplars).

Hatch explained that À A B L W G D P and nearly all minuscules support αὐτῶν, and αὐτῶν is also supported by the Peshitta and by the Harklean Syriac, the Ethiopic, Armenian, and Gothic versions. He observed that Codex Bezae (D, 05) has neither αὐτῆς nor αὐτῶν, but αὐτοῦ (“his”), and at least eight minuscules (listed in a footnote as 21, 47, 56, 61, 113, 209, 220, and 254) have this reading as well. Also, αὐτοῦ is supported by the Sahidic version. Latin texts are rather ambiguous on this point, whether Old Latin or Vulgate; the Latin eius can be understood as masculine or feminine (but not plural). Hatch also noted that “A few authorities have no pronoun at all after καθαρισμοῦ,” but he did not specify which ones.

Hatch advocated a

relatively not-simple hypothesis: that most

of the first two chapters of Luke were “based on a Semitic source” and in this

source, the wording in the passage meant “her” purification but “Luke, or

whoever translated the source into Greek, having read in the preceding verse

about the circumcision and naming of Jesus, took it as masculine, ‘his

purification,’ and translated it by καθαρισμοῦ αὐτοῦ.”

Hatch proposed, further, that before the time of Origen, someone

realized that αὐτοῦ could not be correct (inasmuch as the

law of Moses says nothing about the purification of male offspring) and changed

it to αὐτῶν.

“Αὐτῆς,” Hatch wrote, “appeared as a learned correction, but its range

was extremely limited until the appearance of the Complutensian edition in

1522.”

Those not willing

to embrace Hatch’s hypothesis may be content to adopt what is in the text of

most manuscripts, whether Alexandrian or Byzantine: καθαρισμοῦ αὐτῶν – “their purification.” Facing D. A. Waite’s contention that texts

with “their purification” are “theologically deficient,” interpreters have at least three

options: to understand

(1) that Luke’s “their purification” is a reference to the custom observed by

followers of Judaism in general, or, (2) that Joseph as well as Mary

participated in the purification-rites, having been in contact with Mary at

Jesus’ birth, or (3) that Joseph accompanied Mary in the purification-rites

even though it was not required by the Mosaic law. In no scenario does the text imply that Jesus

“therefore was a sinner,” inasmuch as the purification-rites commanded

in Leviticus 12 followed ceremonial uncleanness, not sinfulness.