In 1844, the year when Constantine Tischendorf first saw

pages of Codex Sinaiticus at St. Catherine’s monastery, Samuel Tregelles

released An Account of the Printed Text

of the New Testament, a book which had a significant influence among

researchers into the text of the New Testament.

Recently, after discussing Mark 16:9-20 with Stephen Boyce of Explain

International, someone observed that my position (that Mark was permanently interrupted as he wrote 16:8, and someone else attached verses 9-20 (from another composition by Mark) to complete the narrative, before the Gospel of Mark began to be disseminated for church-use, and that verses 9-20 are thus part of the original text) resembled the view of

Tregelles, and it occurred to me that many discussion-viewers might not know

what that means. (I had read Tregelles,

years ago, but on the spur of the moment I couldn’t recall his view in detail.) So here, I have reproduced a large excerpt

from Tregelles’ own statements on the subject, along with a few notes of my

own, from pages 246-261 of An Account of the Printed

Text of the New Testament. I

have not included the footnotes, in the interest of brevity. Some readers, wearied by Tregelles’ thoroughness, may wish to proceed to

Tregelles’ closing comments, which I have marked with “···.”

Tregelles wrote:

“St. Mark xvi. 9-20. The last twelve verses of this Gospel

have some remarkable phenomena connected with their history; in order fully to

discuss their authority, it is needful first to establish by evidence of facts

certain propositions.

I. That it is historically

known that in the early ages it was denied that these verses formed a part of

the Gospel written by St. Mark.

II. That it is certain, on

grounds of historical transmission, that they were from the second century, at

least, and onward, known as part of this book.

III. That the early testimony

that they were not written by St. Mark is confirmed by existing monuments.

After these propositions have been established, the

conclusions to be drawn may assume the form of corollaries.

(I) The absence of this portion from some, many,

or most copies of St. Mark’s Gospel, or that it was not written by St. Mark

himself, is attested by Eusebius, Gregory of Nyssa, Victor of Antioch, Severus

of Antioch, Jerome; and by later writers (especially Greeks), who, even though

they copied from their predecessors, were competent to transmit the record of a

fact.

(i) Eusebius, in the first of his Questiones ad Marinum, discusses πως παρα μεν τω Ματθαιω “οψε

σαββάτων” φαίνεται εγηγερμενος ο σωτηρ, παρα δε τω Μάρκω “πρωι τη μια των

σαββάτων.” [Tregelles then presents an

extract from Eusebius’ composition Ad

Marinum, which is similar to what Roger Pearse presents on p. 96 of Eusebius

of Caesarea: Gospel Problems and

Solutions, and which translates in that book to:

“The

answer to this would be twofold. The

actual nub of the matter is the pericope which says this. One who athetises

that pericope would say that it is not found in all copies of the gospel

according to Mark: accurate copies end

their text of the Marcan account with the words of the young man whom the women

saw, and who said to them: “‘Do not be afraid; it is Jesus the Nazarene that

you are looking for, etc. … ’ ”, after which it adds: “And when they heard

this, they ran away, and said nothing to anyone, because they were frightened.” That is where the text does end, in almost

all copies of the gospel according to Mark. What occasionally follows in some

copies, not all, would be extraneous, most particularly if it contained

something contradictory to the evidence of the other evangelists.” That, then, would be one person’s answer: to

reject it, entirely obviating the question as superfluous.”]

Tregelles continues:

“Eusebius then goes on to explain the supposed difficulty, irrespective

of the supposed authorship of these verses. This testimony, then, is clear, that the

greater part of the Greek copies had not the twelve verses in question. It is evident that Eusebius did not believe

that they were written by Mark himself, for he says, κατὰ Μάρκον μετὰ τὴν ανάστασιν οὐ λέγεται

ὤφθαι τοις μαθηταις. The arrangement of

the Eusebian Canons are also an argument that he did not own the passage; for

in genuine copies of the notation of these sections the numbers do not go

beyond ver. 8, which is marked σλγʹ (233). Some copies, carry indeed, this notation as

far as ver. 14, and some to the end of the chapter; but these are unauthorised

additions, and contradicted by not only good copies which contain these

sections, both Greek and Latin (for instance A, and the Codex Amiatinus), but

also by a scholion found in a good many MSS. at ver. 8, εως ωδε Εὐσέβιος

εκανόνισεν. It has been objected that

these sections show nothing as to the MSS. extant in

Eusebius’s time, but only the condition of the Harmony of Ammonius, from which

the divisions were taken. [It does not seem to have occurred

to Tregelles that Eusebius, after endorsing to Marinus the inclusion of verses

9-20, could have changed his mind when subsequently creating his Canons.] The objection

is not without significance; but it really carries back our evidence from the

fourth century to the third; and thus it is seen, that just as Eusebius found

these verses absent in his day from the best and most numerous copies, so was

also the case with Ammonius when he formed his Harmony in the preceding

century.”

[That

the “Ammonian Sections” are the work of Eusebius, and not Ammonius, was later demonstrated

by John Burgon in Appendix G of his 1871 book, The Last

Twelve Verses of the Gospel According to S. Mark Vindicated Against Recent

Critical Objectors and Established.]

[Tregelles

then reviews the testimony from Gregory of Nyssa – which, subsequent to

Tregelles, was regarded as the work of Hesychius – and Victor of Antioch, noting

that Victor’s remark] “is worthy of

attention; for his testimony to the absence of these twelve verses from some or

many copies, stands in contrast to his own opinion on the

subject. He seems to speak of having

added the passage in question (to his own copy, perhaps) on the authority of a

Palestinian exemplar.”

Next, Tregelles reviews a statement from Severus of

Antioch, and says, “This testimony may

be but a repetition of that already cited from Gregory of Nyssa; but if so, it

is, at least, an approving quotation.”

“It is worthy of remark that both Eusebius and Victor have τῇ

μιᾷ where our text has πρώτη; this may

be an accidental variation; as they do not afterwards give the words precisely as they had before quoted

them; or it may show that they spoke of the passage, ver. 9-20, without having

before them a copy which contained it, and thus that they unintentionally used τῇ

μιᾷ as the more customary phraseology in the New Testament.

“Dionysius of Alexandria has been brought forward as a

witness on each side. Scholz refers to

his Epistle to Basilides, as though he had there stated that some, or many,

copies did not contain the passage;

and Tischendorf similarly mentions his testimony; while, on the other hand, Dr.

Davidson (Introd. i. 165) places Dionysius amongst those by whom the passage “is

sanctioned.” All, however, that I can

gather from his Epistle to Basilides (Routh, Rel. Sac. iii. 223-32) is, that in

discussing the testimony of the four evangelists to the time (whether night, or

early in the morning) at which our Lord arose from the dead, he takes no notice whatever of Mark xvi.

9; and this he could hardly fail to have done, as bearing more closely on the

question, when referring to the beginning of the same chapter, if he had

acknowledged or known the last twelve verses. His testimony, then, quantum valeat, is purely negative.

“Jerome’s testimony is yet to be adduced. He discusses (Ad Hedibiam, Qusest. II. ed.

Vallarsi, i. col. 819,) the difficulties brought forward as to the time of the resurrection. “Hujus

qusestionis duplex solutio est; aut enim non recipimus Marci testimonium, quod in raris fertur Evangeliis, omnibus

Grceciae libris pene hoc capitulum in fine non habentibus, praesertim quum

diversa atque contraria Evangelistis caeteris narrare videatur ; aut hoc

respondendum, quod uterque verum dixerit,” etc. He then proposes to remove the difficulty by a

different punctuation, in the same manner as Eusebius and Victor did.”

“But an endeavour has been made to invalidate Jerome s

testimony by referring to what he says in his Dialogue against the Pelagians,

II. 15. “In quibusdam exemplaribus, et maxime in Græcis codicibus juxta Marcum

in fine ejus Evangelii scribitur: Postea

quum accubuissent undecim apparuit eis lesus, et exprobravit incredulitatem et

duritiam cordis eorum, quia his qui viderant eum resurgentem non crediderunt. Et illi

satisfaciebant dicentes; Sæculum istud iniquitatis et incredulitatis substantia* est, quæ non

sinit per immundos spiritus veram Dei apprehendi virtutem: idcirco jam nunc

revela justitiam tuam. Cui si

contradicitis, illud certe renuere non audebitis; Mundus in maligno positus est,” etc. (Ed. Vallarsi. ij. 744, 5.) Hence it has been inferred that Jerome contradicts himself as to the Greek

copies. But (i.) that conclusion does

not follow, because he may here speak of those Greek copies which did contain

the verses in question, and not of the MSS. in general, (ii.) If this testimony

be supposed to relate to Greek MSS. in general, it is at least remarkable that

we have no other trace of such an addition at ver. 14. [The situation to which Tregelles

alluded changed when Codex W was discovered.] (iii.) Jerome wrote against the

Pelagians in extreme old age, and he made in that work such demonstrable errors

(e. g. citing II. 2, Ignatius instead of Polycarp), that it would be a bold

step if any were to reject an unequivocal testimony to a fact stated in his

earlier writings on the ground of something contained in this; especially when,

if the latter testimony be admitted as conclusive, it would involve our

accepting a strange addition at ver. 14 (otherwise wholly unknown to MSS.,

versions, and fathers) as a reading then

current in Greek copies.

These testimonies sufficiently establish, as an historical

fact, that in the early ages it was denied that these twelve concluding verses

formed a part of the Gospel of St. Mark.

(II.) I now pass to the

proofs of the second proposition;

that it is certain, on grounds of historical transmission, that, from the

second century at least, this Gospel concluded as it does now in our copies.

This is shown by the citations of early writers who

recognise the existence of the section in question. These testimonies commence

with Irenaeus: “In fine autem Evangelii ait Marcus, Et quidem Dominus Iesus, postquam locutus est eis, receptus est in caelos,

et sedet ad dexteram Dei” (C. H. iii. 10. 6). This sentence of the old Latin translator of

Irenseus is thus cited in Greek in confirmation of his having used this part of

the Gospel: Ὁ μὲν ουν κύριος μετὰ τὸ

λαλησαι αὐτοις ἀνελήφθε εις τὸν ουρανόν, καὶ εκάθισεν εκ δεξιων του θεου. Εἰρηναιος ὁ των ἀποστόλων πλησίον ἐν τω πρὸς τὰς αιρέσεις γʹ λόγω τουτο ανήνεγκεν τὸ ρητὸν ὡς Μάρκῳ ειρημένον. [A footnote in Printed Account states that this was

drawn by Cramer from Cod.

Harl. 5647, that

is, minuscule 72. What Tregelles

presented is a combination of 72’s text of Mark 16:19, and the note in 72’s

side-margin.]

“Whether this part of St. Mark was known to Celsus has been

disputed. My own opinion is, that that

early writer against Christianity did, in the passage which Origen discusses

(lib. II. §§ 59 and 70), refer to the appearance of Christ to Mary Magdalen, as

found in Mark xvi. 9; but that Origen, in answering him, did not exactly

apprehend the purport of his objection, from (probably) not knowing or using

that section of this Gospel. This would

not be the only place in which Origen has misapprehended the force of remarks

of Celsus from difference of reading in the copies which they respectively

used, or from his not being aware of the facts to which Celsus

referred.

Tregelles

turns next to Hippolytus, and supplies an extensive quotation from Περὶ Χαρισμάτων Ἀποστολικὴ Παράδοσις “in which this

part of St. Mark s Gospel is distinctly

quoted.”

“After these testimonies of the second and third centuries,

there are many who use the passage; such for instance as Cyril of Jerusalem,

Ambrose, Augustine, Nestorius, (ap. Cyr. Alex. vi. 46.)

Under this head may be mentioned the MSS. and versions in general (the conspectus of their

evidence on both sides will be given under the next proposition); and amongst

the MSS. Those may in particular be

specified which continue the Ammonian Sections on to the end of the chapter. This seems to have been done to supply a

supposed omission; and in ancient MSS., such as C, it is clear that the copyist

took this section for an integral part of the book.

The early mention and use of this section, and the place

that it holds in the ancient versions in general, and in the MSS., sufficiently

show, on historical grounds, that it had a place, and was transmitted as a part

of the second Gospel.

III. To consider properly the

third proposition (that the early

testimony that St. Mark did not write these verses is confirmed by existing

monuments), the evidence of the MSS. and versions must be stated in full.

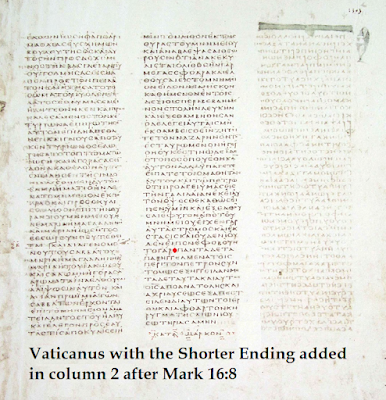

The passage is wholly omitted

in Codex B.,* in the Latin Codex Bobbiensis (k),

in old MSS. of the Armenian, and in an Arabic version in the Vatican (Cod. Arab. Vat. 13). [This was later shown to be an effect of damage to the

manuscript, as Metzger says in a footnote in his Textual Commentary: “Since,

however, through an accidental loss of leaves the original hand breaks off just

before the end of Mark 16.8, its testimony is without significance in

discussing the textual problem.” See

also Clarence Russell Williams’ comments about Cod. Arab. Vat. 13 on p. 398 of

Williams’ The Appendices to the Gospel of

St. Mark, which is contained as the last

essay in Transactions of the

Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, Vol.

18 (Feb. 1915, Yale University

Press).] Of these versions, the Codex Bobbiensis adds a

different brief conclusion, “Omnia autem quaecunque praecepta erant et qui cum

puero [1. cum Petro] erant breviter exposuerunt. Posthaec et ipse jhesus

adparuit. et ab orientem usque. usque in orientem. misit per illos sanctam et

incorruptam (add. praedicationis,

-nem ?) salutis aeternae. Amen.” And the

Armenian, in the edition of Zohrab, separates the concluding twelve verses from

the rest of the Gospel. Mr. Rieu thus

notices the Armenian MSS.; “ἐφοβουντο γάρ·

Some of the oldest MSS. end here

: many put after these words the final Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Μάρκον, and then give

the additional verses with a new superscription, εὐαγγ. κατὰ Μ. Oscan goes on without any break.” The Arabic MS. in the Vatican is that described by Scholz

in his “Biblisch-Kritische Keise” (pp. 117-126); and though the Arabic versions

are of too recent a date to possess much critical value, this MS., so far as

may be judged from the few extracts made, seems to be based on an ancient Greek

text. Besides the MS. which omits the

verses, they are marked with an asterisk in two cursive copies. [The two cursive copies to which

Tregelles referred here are 137 and 138 – neither of

which is as Tregelles described it; both have the Catena Marcum and feature the

comment that alludes to a cherished Palestinian exemplar.]

[Tregelles then reviews the note

in Codex L that appears before the Shorter Ending, and L’s text of the Shorter

Ending.] “Thus far L is supported by the

cursive cod. 274, by the marg. of the Harclean Syriac, and by the Latin Codex

Bobbiensis (see above). L then continues : “ἔστην [i. e. -τιν] δὲ καὶ ταυτα φερόμενα μετὰ τὸ Ἐφοβουνται γάρ” ~ - - - - - - - ~ ἀναστὰς δὲ κτλ. (and then follow the twelve verses).

In Cod. 1, ver. 8 ends on folio 220 A, and at the top of

the next page is written in vermillion, ἔν τισι μὲν των ἀντυγράφων ἕως ωδε

πληρουται ὁ ευαγγελιστής· ἔως ου καὶ

Ευσέβιος ὁ παμφίλου ἐκανόνισεν. ἐν πολλοις δὲ καὶ ταυτα φέρεται (and

then follow ver. 9 20). A similar note or a scholion stating the absence of the

following verses from many, from most, or from the most correct copies (often from Victor or Severus), is found in

twenty-five other cursive codices; sometimes with τελος interposed after ver.

8. The absence of Ammonian divisions in

A L and other good copies after ver. 8 should here be remembered.

Such is the testimony of existing monuments confirming the

ancient witnesses against this

passage.

On the other hand, the passage is found in the uncial codd.

A C D, X Δ, E G Π K M S U V (F is defective); as well as in 33, 69, and the

rest of the cursive copies which have been collated. It is in copies of the Old Latin; in the Vulg. in the Curetonian Syriac, as well as

the Peshito and the Harclean (with the marginal note given above), and the

Jerusalem Syriac; in the Memphitic, Gothic, and Æthiopic; besides those which

have been previously mentioned as characterised by some peculiarity. The Thebaic is here defective, but it is

supposed that a citation in that language may be a

paraphrase of ver. 20. The Gothic is

defective in the concluding verses, but enough is extant to show that it

recognised the passage; [The

final page of Mark in the Gothic manuscript Codex Argenteus, containing verse

12-20 of the sixteenth chapter, was not recovered until 1970, when Franz

Haffner found it in St. Afra’s Chapel in the cathedral

in Speyer, Germany.] and of the Curetonian Syriac no part of this Gospel

is found except a fragment containing ver. 17 to the end of this chapter.

The Old Latin is here defective in the best copies; for the

Codex Vercellensis is imperfect from ch. xv. 15, and Cod. Veronensis from xiii.

24. Also the Cod. Brixianus is defective

from xiv. 70. The mode in which Cod.

Bobbiensis concludes has been noticed already. The Codices Colbertinus,

Corbiensis, and others, are those which may be quoted as showing that the Old

Latin contains this section.

It has been suggested that this portion of St. Mark was omitted by those who found a difficulty

in reconciling what it contains with the other Evangelists. But so far from there being any proof of this,

which would have required a far less change, we find that the same writers who

mention the non-existence of the passage in many copies, do

themselves show how it may be harmonised with what is contained in the other

Gospels ; we have no reason for entertaining the supposition that such a

Marcion-like excision had been here adopted.

In opposing the authenticity of this section, some have

argued on the nature of the contents;‒ that the appearance of our Lord to Mary

Magdalene first, is not (it is said)

in accordance with what we learn elsewhere; that the supposition of miraculous

powers to be received (ver. 17, 18) is carried too far; that (in ver. 16) Baptism is too highly exalted. I mention

these objections, though I do not think any one of them separately, nor yet the whole combined, to be of

real weight. There is no historical difficulty which would be regarded as of

real force, if, on other grounds, doubt had not been

cast on the passage; for else we might object to many Scripture narrations,

because we cannot harmonise them, owing

to our not being acquainted with all the circumstances. As to the doctrinal

points specified, it is hard to imagine what difficulty is supposed to exist; I

see nothing that would involve the feelings and opinions of an age subsequent

to the apostolic.

The style of

these twelve verses has been relied on as though it were an argument that they

were not written by Mark himself. I am

well aware that arguments on style

are often very fallacious, and that by

themselves they prove very little; but when there does exist external

evidence, and when internal proofs as to style, manner, verbal expression, and

connection, are in accordance with such independent grounds of

forming a judgment, then these internal considerations possess very great

weight.

A difference has been remarked, and truly remarked, between

the phraseology of this section and the rest of this Gospel. This difference is in part negative and in

part positive. The phraseology of St. Mark possesses characteristics which do

not appear in these verses. And besides

these negative features, this section

has its own peculiarities; amongst which may be specified πρώτη σαββάτω (ver.

9), instead of which τη μια των σαββάτων would have been expected: in ver. 10

and 14 sentences are conjoined without a copulative, contrary to the common

usage in St. Mark. εκεινος is used four

times in a manner different from what is found in the rest of the Gospel. The periodic structure of verses 19 and 20 is

such as only occurs once elsewhere in this Gospel (xiv. 38).

Many words, expressions, and constructions occur in this

section, and not in any other part of St. Mark: e. g. πορεύομαι (thrice), θεάομαι (twice), απίστεω

(twice), ἕτερος, παρακολουθέω, βλάπτω, επακολουθέω, συνεργέω, βεβαιόω,

πανταχου, μετὰ ταυτα, εν τω ονοματι, ὁ κυριος, as applied absolutely to Christ

(twice). Now, while each of these

peculiarities (except the first) may possess singly no weight, yet their combination, and that in so short a

portion, has a force which can rather be felt

than stated. And if any parallel be attempted, as to these

peculiarities, by a comparison of other portions of St. Mark, it will be found

that many chapters must be taken together before we shall find any list of

examples as numerous or as striking as those which are crowded together here in

these few verses.

These considerations must be borne in mind as additional to

the direct evidence stated before.

It has been asked, as an argument that the section before

us was actually written by St. Mark, whether it is credible that he could have

ended his Gospel with . . . ἐφοβουντο γάρ. Now, however improbable, such a difficulty

must not be taken as sufficient, per se,

to invalidate testimony to a fact as such. We often do not know what may have

caused the abrupt conclusion of many works. The last book of Thucydides has no proper

termination at all; and in the Scripture some books conclude with extraordinary

abruptness: Ezra and Jonah are instances of this. Perhaps we do not know enough of the

circumstances of St. Mark when he wrote his Gospel to say whether he did or did

not leave it with a complete termination. And if there is difficulty in supposing that the work ever ended abruptly at ver.

8, would this have been transmitted as a fact by good witnesses, if there had

not been real grounds for regarding it to be true? And further, irrespective of recorded

evidence, we could not doubt that copies in ancient times did so end, for B,

the oldest that we have, actually does so. Also the copies which add the concluding

twelve verses as something separate, and those (as L) which give another brief termination, show that

this fact is not incredible. Such a peculiarity would not have been invented.

It has also been urged with great force that the contents

of this section are such as preclude its having been added at a post-apostolic

period, and that the very difficulties which it contains afford a strong

presumption that it is an authentic history: the force of this argument is such

that I do not see how it can be avoided; for even if a writer went out

of his way to make difficulties in a supplement to St. Mark’s Gospel, it is but

little likely that his contemporaries would have accepted and transmitted such

an addition, except on grounds of known and certain truth as to the facts

recorded. If there are points not easy

to be reconciled with the other Gospels, it is all the less probable that any

writer should have put forth, and that others should have received, the

narrative, unless it were really authentic history. As such it is confirmed by the real or supposed points of

difficulty.

As, then, the facts of the case, and the early reception

and transmission of this section, uphold its authenticity, and as it has been

placed from the second century, at least, at the close of our second canonical

Gospel; and as, likewise, its transmission has been accompanied by a continuous

testimony that it was not a part of the book as

originally written by St. Mark; and as both these points are confirmed by

internal considerations―

The following corollaries flow from the propositions

already established:‒

[···]

I. That the book of

Mark himself extends no farther than ἐφοβουντο γάρ, xvi. 8.

II. That the remaining twelve verses, by whomsoever

written, have a full claim to be received as an authentic part of the second

Gospel, and that the full reception of early testimony on this question does

not in the least involve their rejection as not being a part of Canonical

Scripture.

It may, indeed, be said that they might have been written

by St. Mark at a later period; but,

even on this supposition, the attested fact that the book once ended at ver. 8

would remain the same, and the assumption that the same Evangelist had added

the conclusion would involve new difficulties, instead of removing any.

There is in some minds a kind of timidity with regard to

Holy Scripture, as if all our notions of its authority depended on our knowing

who was the writer of each particular portion; instead of simply seeing and

owning that it was given forth from God, and that it is as much his as were the

commandments of the Law written by his own finger on

the tables of stone. As to many books of

Scripture, we know not who the writers may have been; and yet this is no reason

for questioning their authority in the slightest degree. If we try to be certain as to points of which there is no proof, we really shall

find ourselves to be substituting conjecture in the place of evidence. Thus some of the early Church received the

Epistle to the Hebrews as Holy Scripture; who, instead of absolutely

dogmatising that it was written by St. Paul ‒ a point of which they had no

proof ‒ were content to say that “God only knoweth the real writer”: and yet to

many in the present day, though they have not one whit more evidence on the

subject, it seems, that to doubt or disbelieve that Epistle to have been

written by St. Paul himself, and to doubt or disbelieve its canonical

authority, is one and the same thing. But

this mode of treating Scripture is very

different from what ought to be found

amongst those who own it as the word of God.

I thus look on this section as an authentic anonymous

addition to what Mark himself wrote down from the narration of St. Peter (as we

learn from the testimony of their contemporary, John the Presbyter); and that

it ought as much to be received as part of our second Gospel, as the last

chapter of Deuteronomy (unknown as the writer is) is received as the right and

proper conclusion of the books of Moses.

I cannot but believe that many upholders of orthodox and

evangelical truth practically narrow their field of vision as to Scripture by

treating it (perhaps unconsciously) as though we had to consider the thoughts,

mind, and measure of apprehension possessed personally by each individual

writer through whom the Holy Ghost gave it forth. This is a practical hindrance to our receiving

it, in the full sense, as from God; that is, as being really inspired: for, if inspired, the true and

potential author was God, and not the individual writer, known or

anonymous.

We know from John the Presbyter just enough of the origin

of St. Mark’s Gospel to be aware that it sprang from the oral narrations of the

Apostle Peter; and we have the testimony of that long-surviving immediate

disciple of Christ when on earth (in recording this fact) that Mark erred in

nothing. But even with this information,

if we thought of mere human authorship, how many questions might be started :

but if we receive inspiration as a fact,

then inquiries as to the relation of human authors become a matter of secondary

importance. It has its value to know

that Apostles bore testimony to what they had seen of Christ’s actions, and

that they were inspired to write as eye and ear witnesses of his deeds and

teaching. So it is of importance to know

that in this Gospel we have the testimony of Peter confirmed by John the

Presbyter; but the real essential value of the record for the continuous

instruction of believers, is that inspiration of the Holy Ghost which constitutes

certain writings to be Holy Scripture.

Those which were originally received on good grounds as such, and which

have been authentically transmitted to us, we may confidently and reverently

receive, even though we may not know by what pen they were recorded.

To sum up: Tregelles

believed that verses 9-20 were not written by Mark, but that verses 9-20

nevertheless “have a full claim to be received as an authentic part of the

second Gospel,” just as Deuteronomy 34 is received as the proper conclusion of

the books of Moses.