In the Vatican Library, there is a

little-known manuscript, Sir.

162, from the 700s, which is the sole surviving copy of a composition

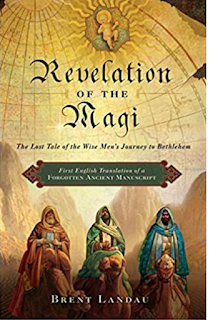

called Revelation of the Magi. Dr. Brent Landau

(Th. D., Harvard Divinity

School), of the University

of Texas at Austin, has studied this text in detail, and

translated it into English. His

translation was published in 2010 by HarperCollins as part of the book The Revelation of the Magi – The

Lost Tale of the Wise Men’s Journey to Bethlehem.

Manuscript Sir. 162 was studied in the

mid-1860s by Otto Tullberg, a Swedish scholar, and Revelation of the Magi was described by M.R. James in 1927 under

the name Liber de Nativate Salvatoris.

A

similar composition is embedded in the Latin composition known as Opus Imperfectum in

Matthaeum, which was produced in the 400s.

When

was Revelation of the Magi

composed? Dr. Landau has proposed that Revelation of the Magi was composed in

Syriac in the late 100s or early 200s, with a later expansion (mainly consisting of the final episode of the book) made in the 300s or 400s.

|

| Dr. Brent Landau |

It is an interesting narrative. Readers who want to learn more about it may

read Dr.

Landau’s book, or the summary here

(the summary of the translation begins on p. 20 of the PDF) or his dissertation (here). My focus is on a specific feature: its use of the contents of Mark 16:9-20.

In Rev. Magi 15:8, there is a

reference to Christ as “the one in whose name signs and

portents take place through his believers.”

This alone would be a strong allusion to Mark 16:17. But even clearer is a passage in 31:10 – part

of the portion which was added in the 300s – where the apostle Thomas (called

“Judas Thomas” in Rev. Magi) is

depicted saying ““Therefore, my brethren, let us fulfill the commandment of our

Lord, who said to us: ‘Go out into the

entire world and preach my Gospel.’”

This is a plain utilization of Mark 16:15 (although in Landau’s

dissertation a footnote treats it as a utilization of Matthew 28:18).

None of which you would learn about

from the apparatus of the Nestle-Aland NTG, or

the UBS GNT, or the Tyndale House GNT (which breaks from its strange practice of presenting no patristic evidence by inserting, between Mark 16:8

and 16:9, an annotation which is taken from minuscule 1.) Yet again the apparatus of Nestle-Aland’s NTG

and the apparatus of UBS’s GNT and the apparatus of the Tyndale House GNT are

silent about a significant piece of early evidence supportive of Mark

16:9-20.

It is no wonder that many preachers

in Europe and America still reject Mark 16:9-20: they have been

misled for over a century by commentators who relied on selective presentations

of the relevant evidence. But hopefully

they will not be so gullible as to continue to trust sources that have

demonstrated their untrustworthiness again and again and again.

4 comments:

Great fine; Keep up the good work. Blessings.

James,

Come on, I know you are convinced about the authenticity of the longer ending of Mark, but to take a wild timeframe estimate from one guy and not only accept it, but condemn the Editions based on that. Your bias and a surprising lack of humility are not a good look

Timothy Joseph,

Instead of accusing Landau of positing a "wild" timeframe (on what grounds??) why not read his Harvard dissertation (see the embedded link), think it over, and *then* tell me what's wrong with his reasoning, eh.

Timothy Joseph,

It was a real invitation.

Post a Comment